Wild Water and Powder Fights Raise Safety and Moral Concerns Ahead of Khmer New Year: Analysts

- By Teng Yalirozy

- April 2, 2024 7:10 PM

PHNOM PENH – With the Khmer New Year coming shortly, early celebrations are kicking off in institutions, pagodas and among the youth, with students taking to the streets to express their excitement ahead of the school break.

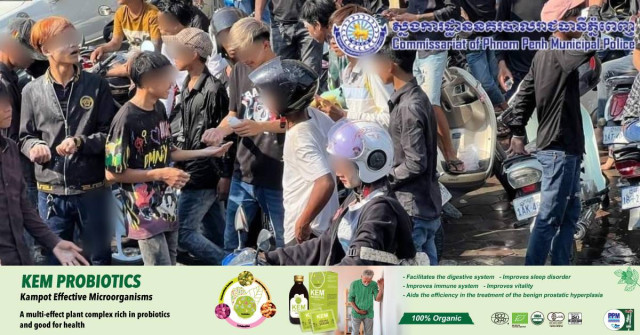

Recently, huge gatherings have been spotted across Phnom Penh with dozens of young Cambodians chasing each other on their motorbikes while playing water games and throwing baby powder at themselves in the streets.

Even though such water and powder games are widespread during New Year’s celebrations, these public gatherings have raised security concerns as they were taking place in the streets, creating traffic jams and increasing the risk of traffic accidents.

On March 31, two videos were shared on Facebook, showing early celebrations of the New Year in Phnom Penh’s streets.

One of them shows dozens of youths driving their motorbikes on Street 271. They are playing water games and covering each other with baby powder while driving their bikes in the middle of the road. Most of them don’t wear a helmet and some passengers are seen standing up at the back of the vehicle.

Another video, also posted on Facebook on March 31, shows a similar gathering on Street 271. On the sidewalk, a massive group of youths is seen overflowing on the road, with a group of about 20 people suddenly crossing the street as part of a chase-tag game, forcing traffic to abruptly stop to avoid any accident.

While no injuries have been reported, these videos have sparked a wave of criticism on social media and raised security concerns as such gatherings took place in public spaces with no regulations, in the middle of Phnom Penh’s dense traffic.

In addition to security matters, some social observers came to question the education these people received, deeming their games as “pathetic” and of “low morality.”

Pa Chamoreun, the head of the Cambodian Institute for Democracy, said he drove through Street 271, in the district of Chomkarmon, while one of these gatherings was taking place.

“It was hard to my eyes to witness such activities of the Cambodian young people,” he said. “There’s no right words to describe them and what they were doing on the street.”

“It can create accidents on the road. Such chaos should not happen in Phnom Penh, the heart of Cambodia” he stressed.

While he claimed such acts show the “deterioration of social morality among the youth,” he pointed out that it is not only the fault of the youth but also of the system they’ve been raised in, including family, school, and friends. They may have not been properly taught civic and moral lessons at schools, he said.

“As seen in Krom Ngoy’s law [the famous Khmer poet in the 19th and 20th centuries], immorality has been deeply injected into the Cambodian society for hundred years,” Chanroeun explained. “But in these past years, the situation has worsened. It’s so pathetic seeing the next generation of the country with low morality.”

Referring to videos showing young men kissing young women on the cheek, he said that touching each other during water and powder games is considered harassment. “Not only it is not a traditional Khmer New Year game, but it is also a criminal offense,” he said.

Is it due to a lack of education?

According to a 2008 study by Charlene Tan, an associate professor at the National Institute of Education in Singapore, the challenges in teaching civic education lie in the contrasting views between traditional and modern education.

While traditional education puts morality at its core, modern education is seen as the means to achieve development and modernization and leaves aside civic education, she said in her research entitled Two Views of Education: Promoting Civic and Moral Values Cambodia Schools.

Tan also pointed out that Cambodian students pay less attention to the subject due to shorter sessions at school, and because they don’t see any real application in their day-to-day lives. Teachers also lack proper training to teach civic and moral lessons, she said.

“For Cambodian students to internalize and apply the civic and moral values learned, they need a conducive social and political culture that goes beyond the classroom environment,” she wrote.

Commenting on the recent gatherings across Phnom Penh, Yang Peou, the secretary-general of the Royal Academy of Cambodia, said water or powder fights can create accidents and endanger the lives of people when done in a disorderly manner.

“This behavior is not good at all, not only harmful but also disgraceful to society,” he said. “This is a social problem for all of us, so if we don't help address it, it can affect us all.”

“Elderly people should not only have words of rebuke but must start to act – set out a specific approach to educating children, correct their mistakes and set an example for them,” said Poeu.

However, Pa Chanroeun remains positive that good behavior in society can be improved if all stakeholders, such as schools and parents, start to strengthen civic and moral education among children and youth.

In response to the recent gatherings across the city, the Phnom Penh Municipal Police ordered the immediate stop of water and powder fights in the public space.

The police have scattered forces across the city to prevent such activities from resuming and said legal action will be taken if the young people do not comply.

Pa Chanroeun encouraged young people to instead play traditional games as a part of preserving and demonstrating the Khmer culture while maintaining the image of society.