Yeang Chheang: Cambodia’s Unsung Hero in the Fight Against Malaria

- By Doug Johnson

- April 25, 2024 10:00 AM

Yeang Chheang may not be a name many people recognize, but in the field of malaria control this 86-year-old Cambodian is a legend.

In 1954, at age 17, Chheang began training as a medical entomologist—his country’s first. During the deadly Khmer Rouge regime in the mid-1970s, he saved countless lives by dispensing malaria medication from his pockets. In the decades after the war, he helped rebuild the country’s shattered malaria control program from scratch.

Today, as Cambodia approaches malaria elimination, Chheang is finally getting the recognition he deserves: In December, he received the “Unsung Hero” award at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai for the sacrifices he made in efforts to eliminate this deadly infectious disease.

Yeang Chheang speaks with USAID and U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative staff at his home in Phnom Penh. Photo_ Polly Woodbury, USAID

Yeang Chheang speaks with USAID and U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative staff at his home in Phnom Penh. Photo_ Polly Woodbury, USAID

“A life of unwavering service to preventing illness and saving lives is an exceptional career worthy of recognition in and of itself,” Dr. David Walton, the U.S. Global Malaria Coordinator at USAID, wrote in a recent letter to Chheang. “To do so through the terror and suffering of the Khmer Rouge regime and to rebuild in its wake is truly heroic.”

Mr. Chheang, a soft-spoken man with wire-rimmed glasses and a razor-sharp memory, has remained humble through it all. One recent muggy afternoon while sipping coconut water in his Phnom Penh apartment, the retired entomologist quietly recounted the horrors and blessings of the seven decades he spent on the front lines of the war on malaria.

Cambodia’s Historic Milestone

For decades, malaria has ranked as one of the most common causes of illness and death in Cambodia, where many of the country’s 17 million residents live and work in rural villages surrounded by dense forests that also are home to malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

But recently, Cambodia has reached an incredible milestone: Not a single malaria death has been recorded in more than six years, and the total number of infection cases in 2023 decreased by two-thirds from the previous year. Suddenly, the dream of eliminating malaria in Cambodia is a real possibility.

Training of malaria staff on microscopy at the malaria laboratory in Phnom Penh in 1981. Mr. Chheang is on the far left. Photo courtesy of Yeang Chheang

Training of malaria staff on microscopy at the malaria laboratory in Phnom Penh in 1981. Mr. Chheang is on the far left. Photo courtesy of Yeang Chheang

No one person or program can take full credit for the turnaround; but together, the Cambodian government; the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), led by USAID and co-implemented with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria have accomplished a great deal. Chheang helped lead control efforts from the very beginning.

Mr. Chheang was born in a rural commune in Kampong Thom Province, where he lived with his parents and four siblings, all of whom would later die in the Khmer Rouge genocide. From a young age, Chheang had a fascination with insects. But it wasn’t until age 17, when a French entomologist at the Institut de Biologie took him under his wing and trained him in vector control, that he decided on his future career path.

“I was fascinated with insects, especially the mosquito which could deliver this powerful disease from its bite,” Mr. Chheang said through an interpreter. “I am forever grateful to (him) for recognizing my interest and training me.”

In 1960, during the rule of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, Mr. Chheang was sent to study in the Philippines. When he returned to Cambodia, he became a 23-year-old entomologist technician at the Ministry of Health’s national malaria control program. He helped initiate the first malaria eradication pilot project in Kratie Province in the 1960s and held a number of senior roles in the malaria program technical bureau when the Khmer Rouge seized power in 1975.

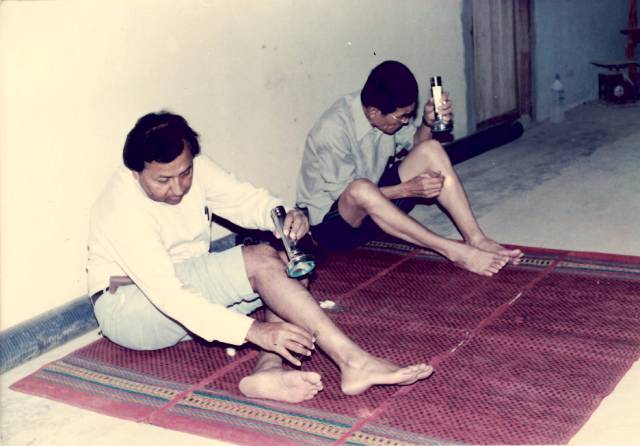

Human landing catch mosquito collection, indoors at night, 1991. Mr. Chheang is on the right. Photo courtesy of Yeang Chheang

Human landing catch mosquito collection, indoors at night, 1991. Mr. Chheang is on the right. Photo courtesy of Yeang Chheang

Sacrifice and Courage

Like most Cambodians at the time, Mr. Chheang experienced horrific loss and sacrifice under the Khmer Rouge. His three brothers, sister, and mother were murdered. His wife and their 10-month-old son starved to death in a labor camp. Mr. Chheang was evacuated by foot to the Preah Net Preah District, but before leaving Phnom Penh he secretly stashed packets of antimalarial pills in his pockets.

At first Chheang tried to keep his pharmacy a secret, fearing retribution from the Khmer Rouge soldiers. But as more prisoners were cured of malaria, the soldiers took notice and demanded treatment for themselves.

Then one day, a top regional military leader became sick and sent for Chheang.

“I was so scared and thought if anything went wrong, I would be killed right there in front of everyone,” he said. Instead, the commander was cured and Chheang gained the respect of fellow prisoners and his captors alike. “After this, they allowed me to move freely from home to home to treat sick people. Anyone with a fever was referred to me.”

While Chheang worked to save lives, Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge killed an estimated two million people from 1975 to 1979, including many doctors and other health professionals. Chheang also lost the majority of his colleagues from the malaria control program.

“I survived the Khmer Rouge because of those malaria tablets. They were my blessing,” he says.

Blood examination for malaria parasites diagnosis at the Malaria Training Center in Praputhabat district, Sarak Bori province, Thailand, in 1991. Mr. Chheang is on the right. Photo courtesy of Yeang Chheang

Blood examination for malaria parasites diagnosis at the Malaria Training Center in Praputhabat district, Sarak Bori province, Thailand, in 1991. Mr. Chheang is on the right. Photo courtesy of Yeang Chheang

Rebuilding

After the war, Mr. Chheang was one of just five malaria workers remaining who returned to Phnom Penh to help restore the national malaria control program—with no budget or staff—from ground zero. He also picked up other pieces of his life and married his late wife’s younger sister, Nong Bunny, who was then a lab technician in the malaria program.

One of his biggest accomplishments at the time, Mr. Chheang says, was organizing a training for 68 participants from 24 provinces to be able to test and treat malaria. Cambodia lacked health care providers, medical equipment and supplies, but Mr. Chheang convinced the World Health Organization in Manila to provide tests, slides, microscopes, and drugs through UNICEF to help the national program get its start.

Partnering with PMI

Mr. Chheang spent many years working alongside USAID-supported PMI projects, including the Malaria Control in Cambodia, or MCC, project in western Cambodia. He would often travel to the Pailin Province near the Thailand border—a former Khmer Rouge stronghold and well-known epicenter of drug resistance and high-burden malaria cases. In Pailin, he led his team on foot for days or weeks through villages riddled with land mines. They took on grave personal risk to identify mosquitoes and their breeding sites, and to deliver treated nets to villagers living there.

, Director of the National Center for Parasitology, Entomology and Malaria Control (CNM), Mr. Chheang (second left), Deputy Director of CNM, and a doctor from Voluntary Service O_1714012288.jpg) Dr. Lek Samdy (left), Director of the National Center for Parasitology, Entomology and Malaria Control (CNM), Mr. Chheang (second left), Deputy Director of CNM, and a doctor from Voluntary Service Overseas (right) discussing the use of Mefloquine to prevent malaria in Pursat, Battambang and Banteay Meanchey provinces in 1992. Photo courtesy of Yeang Chheang

Dr. Lek Samdy (left), Director of the National Center for Parasitology, Entomology and Malaria Control (CNM), Mr. Chheang (second left), Deputy Director of CNM, and a doctor from Voluntary Service Overseas (right) discussing the use of Mefloquine to prevent malaria in Pursat, Battambang and Banteay Meanchey provinces in 1992. Photo courtesy of Yeang Chheang

He would also frequently encounter former Khmer Rouge fighters in the area who had surrendered to government forces and were granted amnesty. Chheang says he treated everyone needing help with the same compassion and respect, regardless of their past. “If we don’t help people with malaria, we cease to be humans.”

An Inspiration to the Malaria Community

Mr. Chheang retired in 2016, but his contributions to the elimination of malaria and his work with the National Center for Parasitology, Entomology and Malaria Control won’t soon be forgotten. Cambodia would not be where it is today without the hard work and dedication of disease control pioneers like Mr. Chheang.

“Your success is an inspiration to me, my colleagues at the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative, and all of the malaria community,” Dr. Walton wrote in his letter to Mr. Chheang. “It is my greatest hope that we can achieve a world free of malaria through the same hard work, dedication, and perseverance.”

About USAID and PMI:

USAID started work on malaria in Cambodia through investments in the Roll Back Malaria Mekong initiative in the year 2000. Funded by USAID, PMI has supported Cambodia’s National Center for Parasitology, Entomology, and Malaria Control (CNM) objectives since 2013 with an overall investment of $87 million. Cambodia remains on track to become the first bilaterally-supported PMI partner country to eliminate malaria.

Doug Johnson is a Development Outreach and Communication Advisor at USAID Cambodia.