Writer lifts Veil on Exiles' Troubled Spirits

- By François Camps

- March 18, 2023 10:25 AM

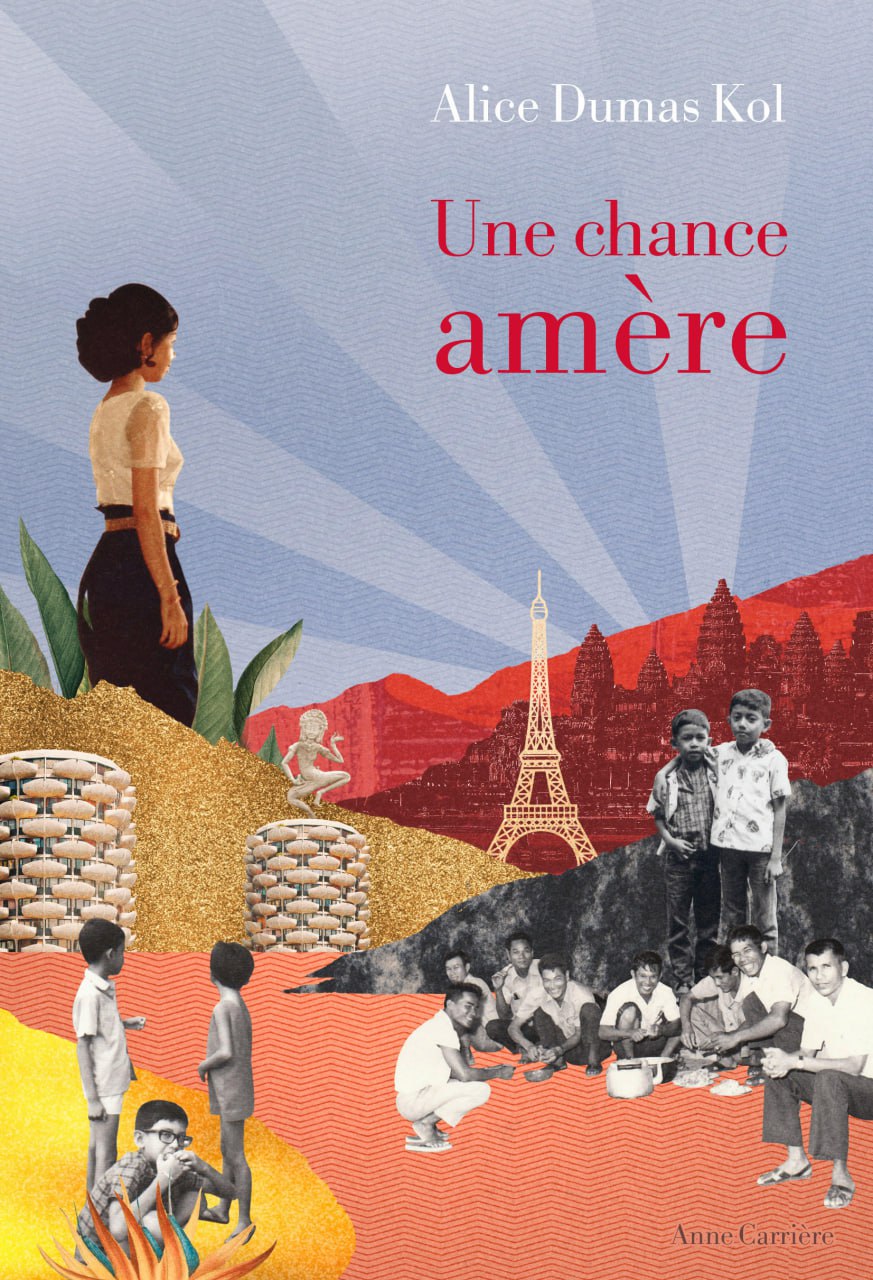

PHNOM PENH – Being a descendant of a refugee family offers its share of resentment and identity crises. In her first book, Alice Dumas Kol, a 33-year-old French offspring from the Khmer diaspora, offers a very personal view of the history of her own Cambodian family, whose destiny — like that of all Cambodian families — changed dramatically on the morning of April 17, 1975.

That day, her grandparents from the Khmer upper class took their children on a boat off the coast of Sihanoukville to escape the Khmer Rouge regime that was about to embark on mass killings, especially people from their ranks.

By doing so, “Yeay” and “Ta” (grandmother and grandfather in Khmer) offered their children and not-yet-born grandchildren a life, a new chance in France. But the difficult choices made that day, and the rocky path towards integration pursued the family over three generations.

In her 160-page book, “A Bitter Luck” — “Une chance amère” in its original version — Alice Dumas Kol portrays some of the women of her family: her grandmother, her mother, and herself. Her sharp and striking writing conveys the author’s relationship with the tortuous history of her family.

François Camps: Is it easy to write a book about your own family?

Alice Dumas Kol: There is a cathartic effect in writing. Clearly, what I wrote is not always joyful, but I felt the need to explore my family’s history for a very long time. I have been having these images and fantasies about some very dark moments in my family’s history and digging into it was liberating.

On the other hand, the stories I tell in the book have been lived by people who are still alive, and thinking that I’m publicly writing about what happened in the middle of the 1970s is troubling. It’s not easy to deal with people’s feelings.

François Camps: Who is this book for?

Alice Dumas Kol: I’d like it to reach the largest audience possible, mostly in the French-speaking world [no translation of the book is planned so far]. I want readers to understand more about minorities, these people that have been through exile, and what it can represent for the following generations. I wrote the book with the idea of bringing nuances to a larger story and talking about the mixed-raced French-Khmer of my generation.

François Camps: How did the Cambodian community in France receive the book, as it revisits Cambodia’s darkest times, and talks about your personal relationship with that very same community?

Alice Dumas Kol: It is hard to have an objective overview of people’s reactions given not everyone who reads the book tells me what they thought about it. But from what I gathered, I see two different reactions more or less based on generations. First, the generation of my parents, over 50 years old, whose members were kids when they escaped the Khmer Rouge regime with their parents. They tend to question the very essence of my book, asking me what is the point of stirring up painful memories while they have given us — my generation — the chance to grow up in a developed and at-peace country.

The second kind of reaction I received comes from people of my generation, and especially mixed-race people. The questions I raise in regard to my identity, my relationship with the Khmer traditions or Cambodia as a country, and the vision I have of my family’s history … were things that spoke to them. Some of them told me that they’ve also felt these grey areas, these untold stories from their parents and that they appreciated the fact it is now written down in a book.

All along the 160-page book, Alice Dumas Kol’s sharp writing conveys the author’s relationship with the tortuous history of her family.

All along the 160-page book, Alice Dumas Kol’s sharp writing conveys the author’s relationship with the tortuous history of her family.

François Camps: Did you intend to trigger such reactions when you decided to write the book?

Alice Dumas Kol: Not exactly. But I felt I wanted to give myself the right to talk about a story that I didn’t live directly but that still had enormous repercussions on my life. For people of my generation, the trauma experienced by our parents has been infused into our education. The fears they have had following the exile, like their fearful approach to others, have somehow been transmitted to us. I didn’t live the atrocious facts they’ve been through but I lived their echoes on me. The purpose of the book is to say: “It impacted me as well.”

François Camps: Hence the title of the book, “A bitter luck”?

Alice Dumas Kol: Absolutely. My generation has been lucky to live in a developed and at-peace country, there’s no doubt about it. But that same luck comes with nuances and darker areas. It is not always easy to solely take it from the positive side.

François Camps: Is this where that violence and rage in the writing, that we perceive all along the book, come from?

Alice Dumas Kol: It does. After the passing of my mother, I had a very strong feeling of injustice and that rage surely influenced the way I wrote my book. I wanted it to be coarse, very simple, with no frills. It also comes from this injunction that I’ve always perceived not to go digging into my family’s past because it may hurt.

François Camps: The book somehow portrays several women in your family: Your grandmother “Yeay”, your mother, and yourself. Why did you choose to mostly focus on women?

Alice Dumas Kol: While men in my family are quite silent, women tend to take up a lot of space. They prepare food, they look after the kids and the house … they are more alive! And that life immediately catches the eye much more. After the passing of my mother, I also questioned a lot about what was my legacy on my mother’s side and had the desire of becoming a mother myself. That's why I took the filter of women and women's bodies to talk about my story.

François Camps: What is your relationship with Cambodia?

Alice Dumas Kol: It is a very distant relationship: I’ve only been there three times. I feel a connection but at the same time, I don’t really feel Cambodian, especially because I don’t speak Khmer. I actually feel more Cambodian in France than when I’m in Cambodia. But this feeling is likely true for most of the Cambodian community in France. While the country is changing at a very quick pace and is experiencing unbridled development, Khmer-French people still have a biased and outdated vision that comes from their childhood. But that moment in time dates several decades ago now, and the country has changed since then. Even in the Khmer community in France, the image of Cambodia as a poor and undeveloped country remains. It is a very archaic vision of things.

“A Bitter Luck” portrays several women in the author’s family: her grandmother “Yeay”, her mother, and herself. Photo: Céline Nieszawer

“A Bitter Luck” portrays several women in the author’s family: her grandmother “Yeay”, her mother, and herself. Photo: Céline Nieszawer