The Paris Peace Agreements: 30 Years Later

- By Michelle Vachon

- October 22, 2021 9:27 AM

The international agreements that officially put an end to civil war in Cambodia in October 1991 still reflect challenges that Cambodia faces today, experts say

PHNOM PENH--If there had been any doubt that the war between Cambodia’s government and the Cambodian factions based in Thailand in the 1980s had less to do with that small country’s conflict than those of the superpowers, the conference in Paris that led to the end of the hostilities 30 years ago would have been proof enough.

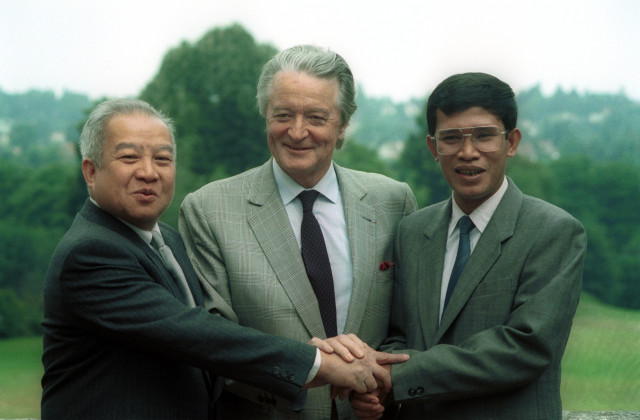

The meeting co-presided by France and Indonesia, which would lead to the signing of the Paris Peace Agreements on Oct. 23, 1991, involved representatives from 16 Asian and western countries—including the superpowers—as well as representatives from the Nonaligned Movement.

Plus representatives of the Cambodian government and Cambodian factions including the Funcinpec of then-Prince Norodom Sihanouk; the Khmer People’s National Liberation Front of Son Sann, a leading political figure of the 1960s; and the Khmer Rouge—factions that had been based in Thailand and had fought the Cambodian government’s forces for a decade.

Even though the conference’s outcome would be less than perfect since the Khmer Rouge would continue their terrorist attacks for seven more years, the Paris Peace Agreements would lead to a national election and a new constitution in 1993 marking the start of reconstruction in Cambodia.

“The first and most important thing of course is that the peace [agreements] ended 20 years of war in Cambodia, 20 very long years,” said US journalist Elizabeth Becker who covered the civil war in Cambodia in the early 1970s and the Paris Peace Agreements conference in Paris in 1991. “It [followed] maybe five years of attempts of Southeast Asian countries, European nations, North American nations, Australia trying to figure out how to end the war.

“It was difficult because Cambodia was the last battlefield of the Cold War,” she said during an online conference on Sept. 15, 2021. “That meant that the Soviet Union had an interest in supporting Vietnam, China was very much behind the Khmer Rouge, the United States was supporting the coalition that included the Khmer Rouge, and KPNLF [of Son Sann, a prominent politician of the 1960s] and Funcinpec [of Prince Sihanouk].

“[I]t was like a Rubik’s Cube, like a puzzle where everybody’s interest had to match before you could manage to make an agreement,” said Becker.

And yet, even though the treaty and the monumental international initiative that would follow—the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC)—would not manage to address all issues Cambodia faced, the treaty would be a defining document, Becker said. Endorsed by the UN and a long list of countries, they reflected, she explained, “the vision they had of what Cambodia could be.”

For the Cambodian population in the country and the refugee camps in Thailand, it was the promise of the end of the nightmare. “[Y]ou wouldn’t be surprised to hear that a lot of Cambodians named their first child UNTAC,” Becker said, as thousands of aid workers came to the country to help rebuild everything from the healthcare system to the road network.

However, as Cambodian Ambassador to the US Chum Sounry pointed out during an online conference held by the US Institute of Peace on Oct. 14, UNTAC would fail to disarm the Khmer Rouge who would continue their guerilla war until their leaders finally surrendered in late 1998.

And the fact that the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) of Prime Minister Hun Sen refused to step down when Funcinpec won the 1993 national elections managed by UNTAC—with Funcinpec obtaining 45 percent of the vote and 58 seats while the CPP got 38 percent of the vote and 51 seats—would create a heated political climate for years to come.

Putting an End to the Cambodia Conflict—a leftover of the Cold War

Cambodia in 1991 was in a dire state.

The Vietnamese forces, which had taken over the country in January 1979 in response to the Khmer Rouge attacking Vietnamese villages along the border, had left Cambodia in September 1989. The Vietnamese government had attempted several times during the 1980s to open negotiations with the United States regarding Cambodia, but without success.

Vietnam, which had been backed by China during its war against the US in the 1960s and early 1970s, had signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union in 1978. This had led China to invade northern Vietnam in February 1979.

The Chinese government had supported the Khmer Rouge throughout the 1970s and continued to do so during the 1980s as the Khmer Rouge fought the Phnom Penh government and Vietnamese armies.

“[T]hrough the war in Cambodia in the 1980s, there was fighting among four principal factions of Cambodians,” said Craig Etcheson during an online conference of the U.S. Institute of Peace on Oct. 14. “But in reality, in many respects, the war in Cambodia was a proxy war being supported by Russia, by the Soviet Union during that period, China and the United States.”

But by the early 1990s, the Cold War that had set these superpowers against one another was over. “So I would argue that the principal purpose of the Paris Peace Agreements was the desire of these great powers to terminate this proxy war and then leave Cambodians to solve their own problems,” said Etcheson, a scientist at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University who served as chief of investigations during the Khmer Rouge tribunal (Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia) in Phnom Penh.

As for the international community pressuring the Cambodian government to respect the terms of the agreement today, Etcheson said, “[e]ven with more than 20,000 troupes and civil servants in Cambodia, the United Nations couldn’t really impose its will in 1991…In terms of protecting human rights with all of those troupes in Cambodia…the human rights component of UNTAC declared that acts of genocide were taking place while they were there, that they prevented, no, that they punished it, no: They just denounced this was happening. So even with 20,000 troupes, the international community could not even impose its will.

“Today, Cambodia knows how to deal with the international community…So my bottom line is that it’s very difficult [if not] impossible for any particular country to get Cambodia to do something that it doesn’t want to do,” Etcheson added.

The signatories of the Paris Peace Agreements may not have looked closely enough at Cambodia’s political history when they negotiated the terms, said Caroline Hughes, chair of Peace Studies at the US University of Notre Dame. “I think the Paris Peace Agreements assumed that establishing an institution that looked like institutions common in Western countries would be sufficient for a democratic polity to spring forward in Cambodia.

“They failed to take note of the deep disorganization of civil society in Cambodia that was a legacy of the war,” she said during the U.S. Institute of Peace conference. “They failed to take effective stance to reduce the significance of the military and violence of military strategies of war. The imbalance between the power of the military and the weakness of civil society have undermined the potential for widening the political space throughout the last 30 years. And because of that, I think we have seen civil society leaders and opposition politicians consistently calling for actual assistance from the signatories of the Paris Peace Agreements to correct this imbalance.

“But that assistance has not been forthcoming particularly since western ideas about democratic enlargement that were prevalent in the 1990s were replaced by much of a counterterrorism [programs] after 2001,” Hughes said, referring to the terrorist attacks conducted by the militant Islamist group al-Qaeda in United States in September 2001.

The Legacy of the Paris Peace Agreements in View of Today’s Context

“When you access the Paris Peace Agreements—the legacy—you have to be balanced and fair,” said Sorpong Peou, a professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration at Ryerson University in Toronto, Canada, who specializes in global governance, security and democracy studies.

“The Paris Peace Agreements made it possible for Cambodia to make a set of transitions from war to peace, from dictatorship to democracy, from poverty to prosperity...I would say the transition from poverty to prosperity is probably the most important one: The country has become a normal, evolving country.

“The Paris Peace [Agreements] was based on a certain, what I would call, pragmatic realism in the sense that…there is no other choice…As someone who went through the civil war and witnessed a lot of violence, [let me say that] Cambodia actually needed peace.” And that meant including the Khmer Rouge in the negotiations,” Peou said during the conference of the U.S. Institute of Peace.

“The UN intervention did not put an end to the armed conflict: The disarmament process was a complete failure,” he said. “It was not until the late 1990s that the Khmer Rouge rebellion ended. And I think the Cambodian government deserves a lot of credit for this positive legacy.

“But there are also negative legacies,” Peou said. “When we are talking about negative legacies, I refer to the worrisome political and legal developments. I do not mean that no progress was made, but that the progress made after the UN intervention has been reversed.

“Cambodia can no longer be considered a multiparty democracy,” he said. “So there has been a transition backward to a one-party democracy…without any credible opposition party since the last election. Human rights have made some progress in some areas when you talk about civil liberties, but not…well protected when you talk about human rights and student civil liberties.

“The Rule of Law is still highly problematic,” Peou said. “The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2020 for instance ranks Cambodia in 127th place among 128 countries. Although I don’t think that this assessment is fair, I still think this assessment gives Cambodia a bad image that must be fixed.” Moreover, he added, state institutions remain deeply politicized and weak.

The Paris Peace Agreements: Goals for the Future?

“To me it is clear that the Paris Peace Agreements is an ongoing document,” said Chak Sopheap, executive director of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights during the U.S. Institute of Peace conference.

“When we talk of peacebuilding process, we have to really understand what peace means,” said Chak Sopheap, executive director of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights. “The Cambodian government often speaks of peace that has been brought back…Nothing wrong about this: We should promote peace.”

However peace, Sopheap said, “does not only mean the absence of the war: It has to build on social harmony among the population, and people have to be able to fully enjoy their fundamental freedom. And that is when we can say it is a complete peace.”

So while it is true that the Paris Peace Agreements did not achieve full peace in the country, the disarmament and re-integration of the Khmer Rouge population into Cambodian society conducted by the Cambodian government toward the end of the 1990s did not mean either that full peace was achieved, Sopheap said.

For Aizawa Nobuhiro, associate professor at Kyushu University in Japan who specializes in Southeast Asian politics and international relations, the hopes and goals set for Cambodia in 1991 cannot be the same as today.

“[W]e should recognize that the bar we set in 1991 and the bar we need to set in 2021 is different because it’s been 30 years,” he said during the conference of the U.S. Institute of Peace. “Like it or not, there are different generations that are becoming the social force of Cambodia. And those new generations may not [give] credit to how Cambodian leaders reached peace…as they might have like to see, for example, more economic and social development and so forth. This happened in Japan too, you know: The leadership of the 1940s [after World War II] could not get the political credit when they were trying to govern in the 1990s. So this is a natural thing.

“But I think the Cambodian process also has to higher the bar,” Aizawa said. “I don’t think the Peace Agreements should be mentioned as either relevant or not relevant. I think it is the foundation…one has to build on top of…And it lies with the people.”

In the years to come, Sorpong Peou of Ryerson University said, “no effective action can be taken if we don’t understand the real challenges, the most important of which is what I call the politics of survival still deeply rooted in the emotionally-charged security environment where political leaders cannot trust each other and cannot find common solutions.

“Most experts like to talk about the country of opportunity that has been Cambodia,” he said. “But I always like to focus on the culture of mutual distrust and retribution that must be overcome. So in short, while this agreement laid a good foundation upon which we, the Cambodian people, can build a better future for ourselves and our children, it would not be easy for them to achieve this objective because Cambodian politics has been complicated by global and regional politics as well.

“And that is another challenge for Cambodia,” Peou concluded.