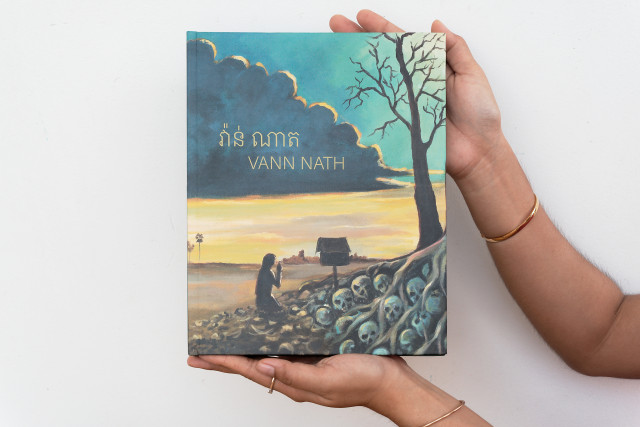

The Book “Vann Nath” Is Released to Mark the 10th Anniversary of the Cambodian Painter’s Death

- By Michelle Vachon

- March 13, 2022 5:20 PM

One of the rare prisoners to survive S-21, his work helped Cambodians and foreigners grasp the extent of the Khmer Rouge atrocities

PHNOM PENH--Like many Cambodians who lived through the Khmer Rouge regime, the parents of Jean-Sien Kin had never told him what they had seen and suffered during those years.

It is only when he came across a painting done by Vann Nath in the 2000s that he realized what the Pol Pot regime had done to its own people, he said. Vann Nath had been kept alive at the extermination camp referred to as S-21 so he could paint portraits of the regime’s leader Pol Pot.

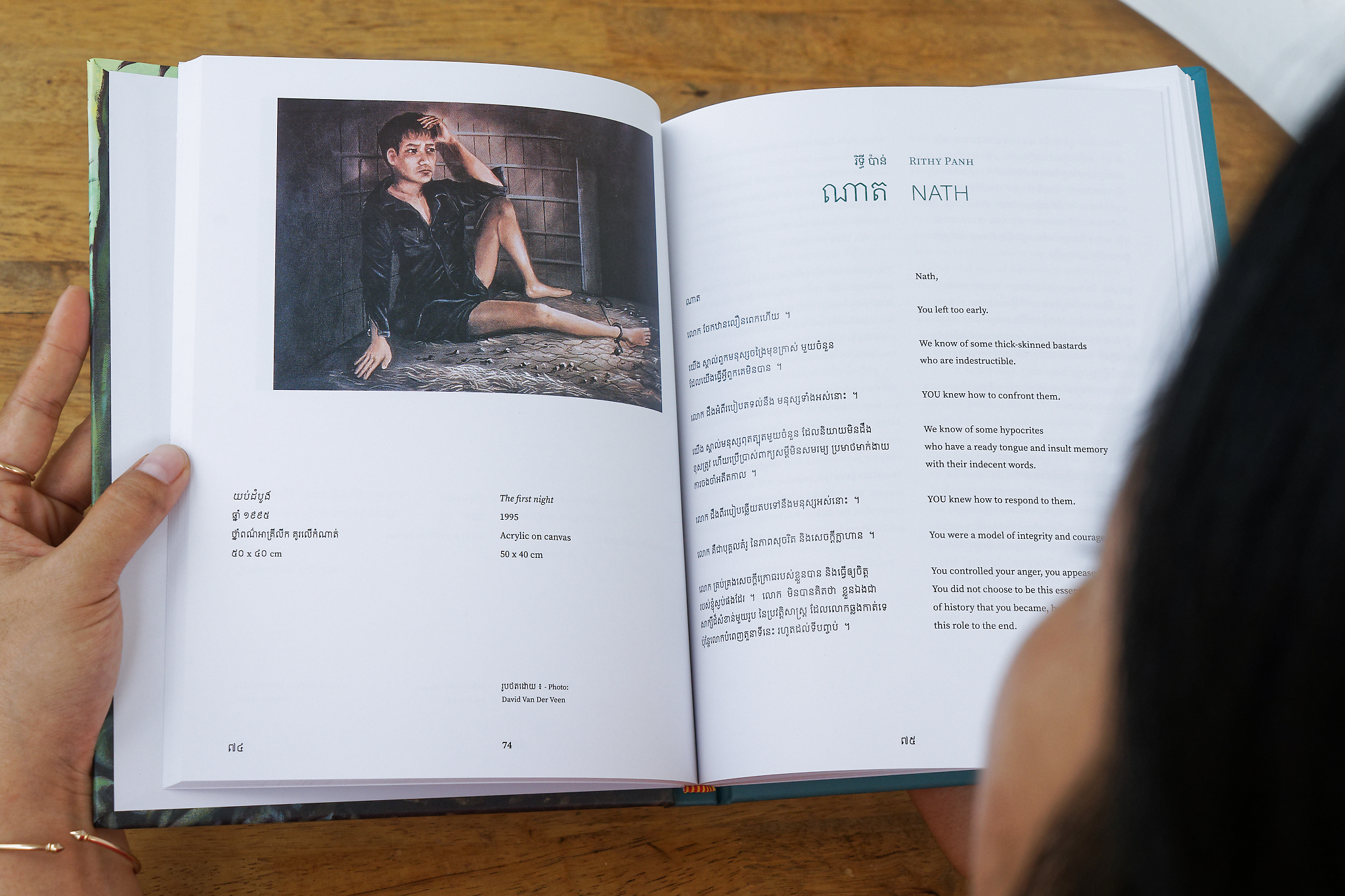

One of the very few people to survive S-21, Vann Nath painted scenes that made the general public understand the barbary of the Khmer Rouge who had taken over the country in April 1975 and were finally driven out in January 1979.

Kin, who was born in late 1979 in France where his parents had immigrated a few months earlier, met Vann Nath in 2006. He would later launch with two friends the group Cercle des Amis de Vann Nath (Vann Nath’s circle of friends) in France to collect money to help pay the artist’s medical care—he had a kidney disease and needed regular treatments.

Vann Nath died in September 2011 and, to mark the 10th anniversary of this death a few months ago, Kin and the group have released a book on his paintings. Simply entitled “Vann Nath” and written in English and Khmer, it was published with the support of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, and private sponsors.

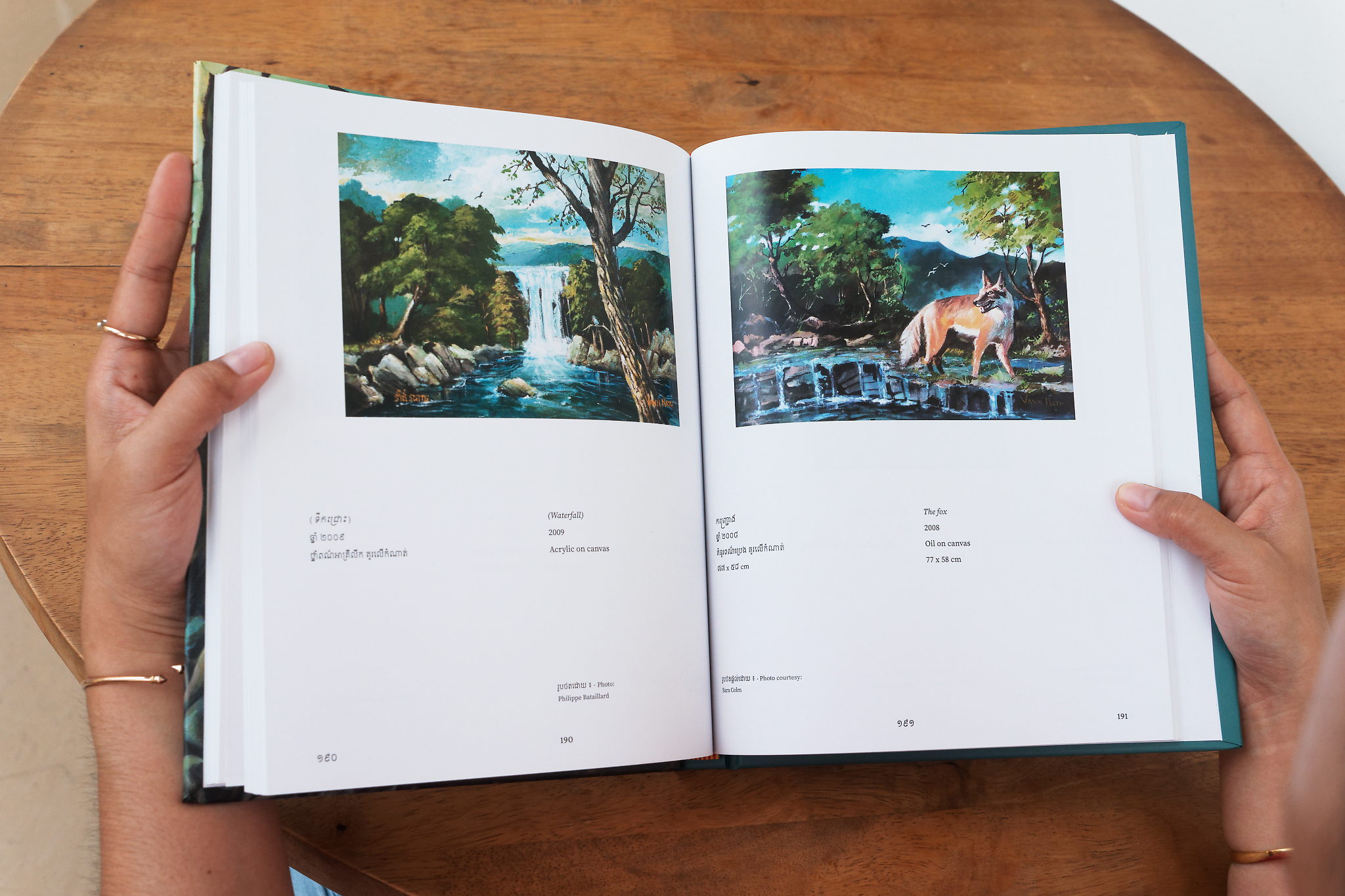

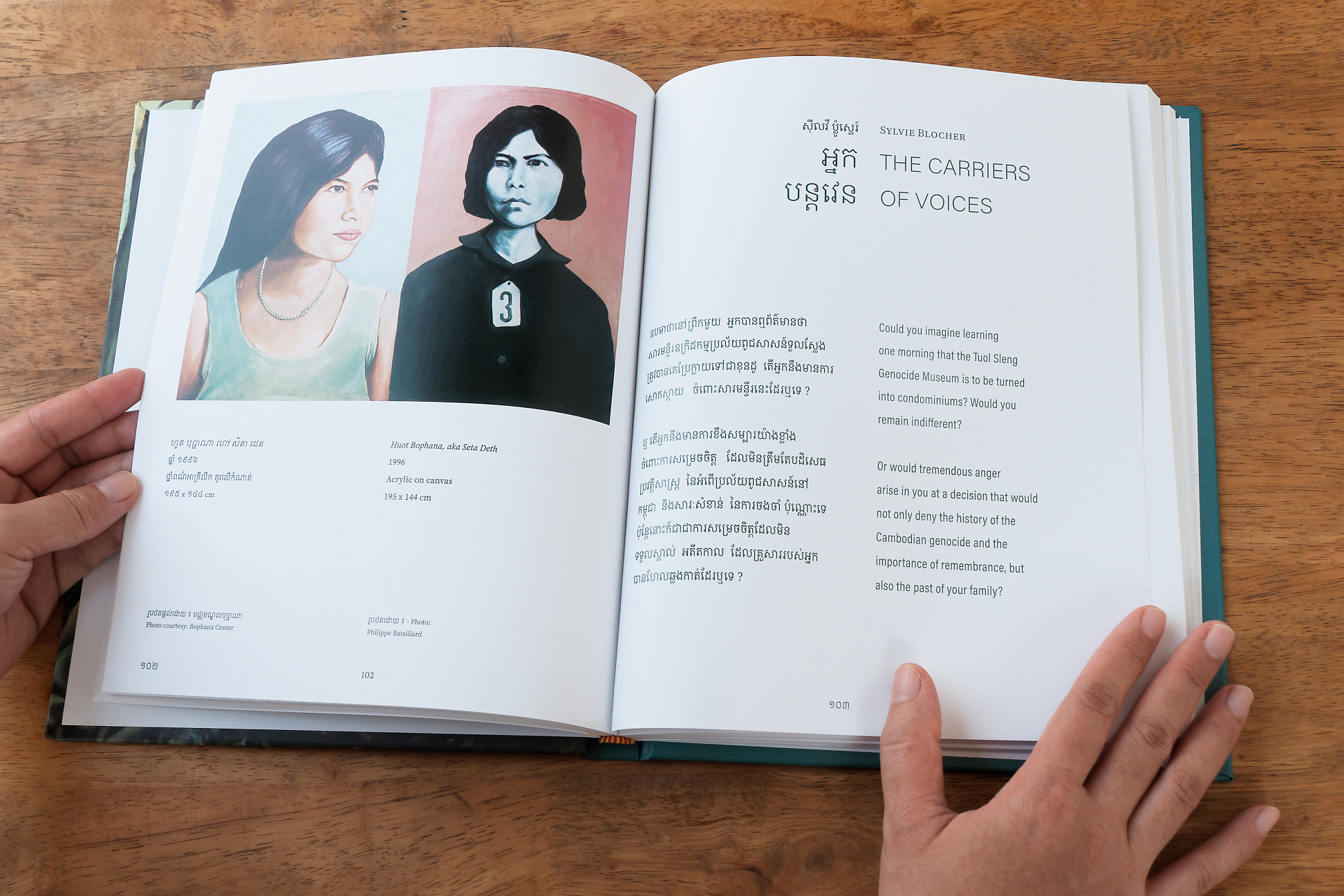

Officially launched in Phnom Penh at the Bophana Audiovisual Resources Center on March 11, the 240-page work features Vann Nath’s paintings that are on permanent display at the Tuol Sleng museum as well as works acquired by collectors across the world, said Kin on March 11.

“Most of the people who have Vann Nath’s paintings live abroad,” Kin said. “So, the major part of the work [for the book] was to locate the paintings, contact the owners, ask for their cooperation and for good quality photos.” Most collectors agreed and photos of the painter’s works were sent from France, Germany, Norway, Singapore, Switzerland, and United States by European, US as well as Cambodian collectors, Kin said.

A graphic designer by profession, Kin had first discussed this book project with Vann Nath in 2009 and had hoped to have it published while the artist was still alive. “To my great regret,” he said, “this did not happen.” But Kin remained determined to have this book released. “It’s a promise I had made,” he said.

Vann Nath was born in Battambang Province in 1946. Seriously ill when he testified at the trial of Tuol Sleng director Kaing Guek Eav, known as Duch, in June 2009, the painter was able to see Duch found guilty the following year by the Khmer Rouge Tribunal—that is, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia.

As art curator Reaksmey Yean explains in the book, Vann Nath’s paintings of Tuol Sleng have provided “the missing pictures” that helped people grasp the atrocities that the Khmer Rouge committed, the same way that Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh used sculpted figurines in his film “The Missing Picture” to recreate scenes he remembered taking place during the regime but for which there is no visual record.

And yet, Vann Nath’s work was not solely about the inhumanity of the Pol Pot regime, Yean said. “Vann Nath’s works that have not deployed the historical trope of the genocide, such as [his painting] “Praying for Peace” …constitute the artist’s fight for peace: A fight, to borrow Jean-Sien Kin’s terms [said in conversation], ‘that would not involve other weapons than those of empathy, solidarity, resiliency, courage, and hope.’

“And I would add, self-mastery,” Yean said. “However…one may ask whether the Khmer Rouge theme could have escaped Vann Nath’s artistic vocabulary. Has he ever attempted to omit or overcome the haunting memory in those paintings, the ones that do not bear the macabre scene? Or does every single piece of his works need to be necessarily interpreted through the prism of the Cambodian tragedy? If anything at all that the…analysis [of his paintings] confirms is how religious and Buddhist philosophy informs the artist’s production.”

In other words, no matter how hard the Khmer Rouge tried to destroy Cambodians’ soul through the atrocities they inflicted, they did not succeed: Vann Nath’s work may show the cruelty of the regime but it also indicates that this did not shatter his and people’s spirit.

And in spite of what he had lived through and his sickness during his last years, Vann Nath retained a willingness to explore. In early 2011, when a group of Mexican artists led by Fernando Aceves Humana brought to the Royal University of Fine Arts (RUFA) the first lithography press—a 390-kilogram piece of metal equipment arrived on a ship—ever seen in the country, Vann Nath was among the established artists who got curious about it and designed works to be lithographed. Art students at RUFA were somewhat in awe when they saw him discretely looking at the press one day.

The first indication of what the Pol Pot regime had been that Jean-Sien Kin found was a painting of Vann Nath he saw on the internet: It depicted two Khmer Rouge guards carrying a man attached to a bamboo stick by his arms and legs as if he was an animal to be roasted. “For me, Vann Nath [work] was a door opening on this troubled past that my parents could not manage to communicate,” he said.

Vann Nath, who featured in the 2002 film “S21, the Khmer Rouge Killing Machine,” of Rithy Panh, was awarded France’s Knight of Arts and Culture in 2004, and the Human Rights Watch’s Hellman/Hammett Award for persecuted writers in 2002 and 2007.

The public launch of the book “Vann Nath” took place March 14 at the art gallery Silapak Trotchaek Pneik, which is located at the YK Art House, 13 A Street 830 in Phnom Penh.

The book remains available at the gallery.