Takakazu Yamada -- A Lifelong Love Affair with Cambodia

- Michelle Vachon

- December 17, 2019 4:23 AM

When Japanese artist Takakazu Yamada first visited Angkor Wat, there were armed soldiers guarding the 1,000-year-old monument.

This being 1994, military divisions with guns and tanks were guarding the Angkor Archeological Park against the Khmer Rouge. “But I did not feel in danger,” Yamada said. “Those armed soldiers at Angkor Wat, I could feel their warm personalities.

“I wanted to come back to sketch,” he said. But it is only in 1999—the last Khmer Rouge leaders having finally put down their arms in late 1998—that Yamada would be able to get a visa to return.

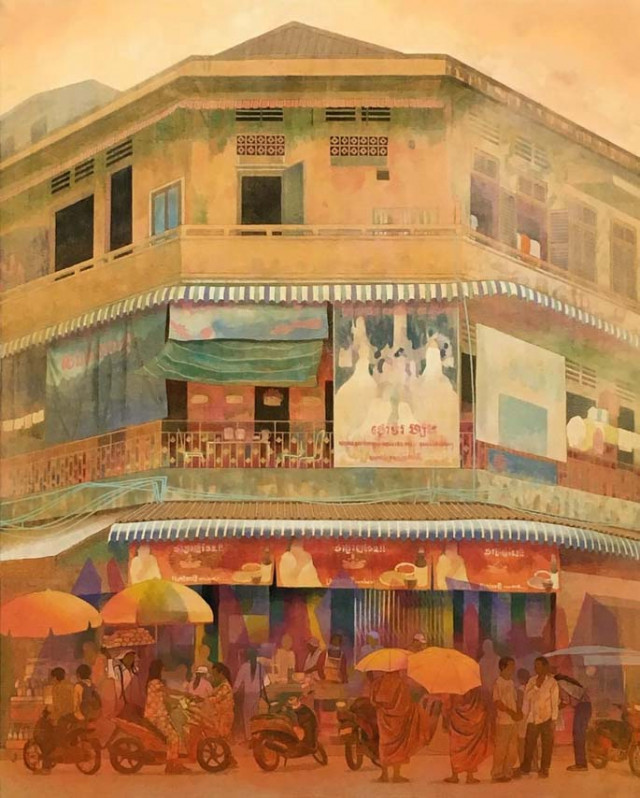

Since then, he has split his time between Japan and Cambodia, an artist and university art teacher in both countries, using traditional Japanese art techniques to portray today’s Cambodia from Phnom Penh’s busyness to its centuries-old monuments.

As can be seen in his exhibition currently held at The Gallery of Sofitel Phnom Penh Phokeethra hotel in Phnom Penh.

Entitled “Memory,” it includes a vast cityscape of Phnom Penh illustrating the busyness one can see every day along its streets, to a small river zigzagging through Cambodia’s flat landscape, and a young girl at the foot of a huge centuries-old tree at the Ta Prohm monument at Angkor.

Because even though Angkor was love at first sight for him, it is the people who have made him return to the country year after year since 1999.

Starting with villagers living at Angkor.

Japanese artist Takakazu Yamada in The Gallery of hotel Sofitel where his paintings are exhibited. Photo Michelle Vachon

Getting to know Angkor and its people

Born in 1957 in Nagoya in Japan, Yamada studied Japanese traditional-painting techniques at the Aichi Prefectural University of the Arts.

A university art teacher in Japan, for 15 years his work also included being part of a university project to draw accurate reproductions of 400-year-old artworks that are considered Japanese national treasures and may deteriorate as centuries go by. He also served as an advisor to the Japan Art Institute for more than 20 years.

This, however, did not prevent him from coming to Cambodia every year from 1999 on, at first mainly to sketch monuments at Angkor.

That year and in the early 2000s, there were relatively few visitors at the monuments—which may be difficult to imagine nowadays—and at times, there only were at a monument Yamada who sketched all day and children from the villages inside Angkor park selling souvenirs.

Since he was more or less sharing their space, Yamada would buy small items from them as a thank-you for letting him be there. In the process, Yamada came to know the children’s mothers and fathers, uncles and cousins who adopted him. So much so, he said, that when he returned one year, making the trip by bus from Phnom Penh, there were around 40 people waiting for him at the bus stop. No doubt Cambodia’s powerful information network had been at work, as in an employee of the guest house where he had made a reservation telling his cousin who happened to be a nephew by marriage of the mother of one of the kids in an Angkor park village.

Then in 2007, Yamada became a guest teacher at the Royal University of Fine Arts and also opened in Phnom Penh his Yamada School of Art. Highly respected by students, he teaches them the importance of sketching on site rather than from a photograph. Because nothing is truly static, he says, if only the intensity of light in a scene as hours go by. He also insists that students learn to sketch whether or not they plan to focus on abstract painting at some point.

Takakazu Yamada’s painting reflects this tree’s strength and vitality. Photo: Sofitel Phnom Penh Phokeethra.

Ancient techniques to convey the 21th century

Yamada uses traditional Japanese thick paper and colors made out of crushed stones and sand, although he occasionally uses a chemically-made color if this is the only way of obtaining a particular shade, he said.

Colors made of stone tend to quickly wear out the fine brushes he uses. So he keeps a supply of 100 brushes or so in Cambodia.

And since Yamada does what he teaches, he may sit for days to sketch activity on a street corner in Phnom Penh. Then since painting does not have to be true to life, he may build a street scene with elements of several streets to better express the city as he feels it.

For example, one of his large city scenes in the exhibition is obviously Monivong Street in Phnom Penh. However, it actually is a composite of different segments of the street rather than a single section, Yamada said.

As for the time it takes to complete a painting, Yamada may work every day for three to four months to do some of these larger scenes, he said—the details and way he renders light cannot be done in haste.

What is his advice to those who want to paint but keep on waiting for the perfect garden in bloom or a special person willing to be painted.

In fact, Yamada said, “[a]round you in your life…near your house, you can find a good landscape. No need to go very far.”

All it takes is looking, he said. But looking with the eye of an artist.

The exhibition at the Sofitel gallery ends towards the end of January.