Nothing Impossible: Giant Dancing Shiva Statue in 10,000 Pieces Being Reassembled

- By Torn Chanritheara

- March 4, 2024 12:00 PM

SIEM REAP — Behind the red wall of the Department of Safeguarding and Preservation of Ancient Buildings compound—formerly known as the Conservation d’Angkor—in Siem Reap city, a team of Cambodian and French experts are painstakingly restoring a giant statue of a Hindu deity brought from a temple at the Koh Ker archaeological site in Preah Vihear province.

For more than five years, they have been working on this statue, set on reassembling its more than 10,000 pieces, the result of damage caused as recently as 30 years ago. The sculpture, which stands 5-meter high, is a statue of the Dancing Shiva that was in the Krahom temple built in the 10th century during the reign of King Jayavarman IV. In the religious tradition of Brahmanism, the five-face deity posture is meant to destroy ill creatures.

Archaeologist and Department Deputy Director Chhan Chamroeun has led the Cambodian experts working on this project with the team of the French School of the Far East (better known as EFEO, that is, Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient). As he explained, this can be done even though it is a colossal task requiring much more than physical strength and resolve.

“It is difficult but not impossible,” he said during an interview in the workshop in the department compound located along the Siem Reap River. This compound is one of the largest archeological storage facilities in the country built during the French Protectorate in 1910 after the return of the province—along with Battambang and Banteay Meanchey provinces—by Siam to keep stone fragments, sculptures and artefacts found at temples’ sites.

For Eric Bourdonneau, the EFEO project coordinator, assembling this sculpture is both unique and highly meaningful for understanding the history of Cambodia and in particular kingship at the time of Angkor.

“The statue was basically the image of what was named in the 11th century the Devarâja cult,” that is, the cult to the deity in charge of the protection of the kingdom and the king, he said.

According to Chamroeun, larger parts of the statue were scattered inside the Krahom temple and the surrounding area when the French EFEO team first visited in the 1950s. At the time, only the top head and one of the four faces remained, he said.

Then, the fate of the 1,000-year-old statue turned ugly in the early 1990s when the torso was cut off piece by piece by looters using chisels to the extent that, as Chamroeun pointed out, the links between fragments couldn’t be established. Thus, this has made the restoration even more burdensome.

In 2012, the French team started excavating Krahom temple and collected fragments of the statue to store at the Conservation d’Angkor. Among the 10,000 pieces found, approximately 2,500 were stone fragments of the outer skin and clothes of the statue. The team gathered all stone fragments spread inside and outside the temple; some parts of the statue were found as far as 200 meters from the temple, Chamroeun said.

The top head of the statue, one remaining face and the six hands holding things, which had been transported to the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh, were also sent to the Siem Reap workshop for the statue’s restoration.

Thousands of fragments of the statue found in and around Krahom temple at the Koh Ker archaeological site had to be studied to rebuild the statue. Photo: Torn Chanritheara

Thousands of fragments of the statue found in and around Krahom temple at the Koh Ker archaeological site had to be studied to rebuild the statue. Photo: Torn Chanritheara

The Cambodian team working on the project has included stone experts from the National Preah Vihear Authority—the government agency overseeing the Koh Ker archeological site—and from the National Museum in Phnom Penh.

Eight or nine months into the process in 2019, the French and Cambodian experts had managed to assemble parts of the statue. “We had been able to reassemble 60-to-65 percent of the body,” Chamroeun said.

In early 2024, the top head and the six hands were reconnected with the torso.

According to Bourdonneau, there had been two main objectives for restoring the statue of the Dancing Shiva. From a heritage point of view, it is not to let the looters have the last word and to have the public see this unique masterpiece, he said. And from a scientific and historical point of view, it is to find and understand the right position of the Dancing Shiva and, in particular, of the deity’s hands holding the attributes, he said. “It is essential to have this knowledge to have a real understanding of its meaning,” Bourdonneau said.

Never-ending task

The joint team has been working for years to reconnect the various stone fragments to the statue. And the work is still not finished.

Although it takes less time to find the places for the big chunks of stone, the experts first work on the small fragments to put them with other similar parts, Chamroeun explained. Then the larger parts are reassembled, which eventually leads to having a clear picture of the statue, making it easier to restore, he said.

And the team is still reassembling stones. “All theses stones: there is no stone we didn’t try to put up, there is no fingerprint left. It’s lucky that we didn’t need fingerprints this time,” he said jokingly, explaining that the team members tried to piece the statue together without the work involved being too obvious.

Which has been far from easy since, due to the fact that the statue was torn into small pieces, it is hard for the team to find the original places of numerous fragments. “Some pieces are too small and the linkage between them are cut,” Chamroeun said, adding that team has been trying to connect all pieces without leaving out any stone fragment.

But then, assembling the fragments of a section was not always the end of the difficulties. In some cases, he said, “[w]e had put some pieces together but when we tried to affix them to the statue, we couldn’t find the right place.”

The most difficult statue to restore

The statue originally had five faces on a two-level head: one on the top, and four on the right below the top one with 10 hands. Such large statues were rarely erected and hardly found at temples while small sculptures on walls or on the decorative stones of temples can easily be found.

The statue was sculpted using green-gray stone, which is more solid but not as strong as the pink sandstone used, for example, at the Banteay Srei temple in the Angkor Archeological Park.

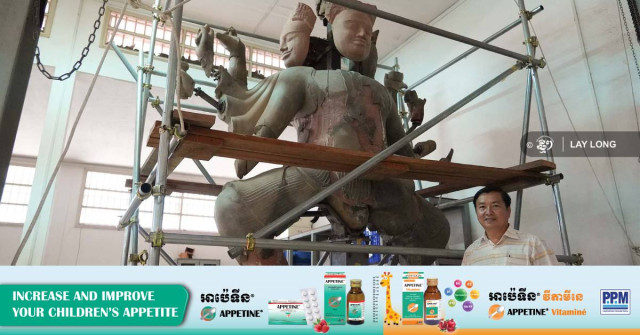

The Cambodian and French team worked on the statue on the grounds of Department of Safeguarding and Preservation of Ancient Buildings compound, previously known as Conservation d’Angkor, where fragments of statues and sculpted features were stored for nearly a century in Siem Reap city. Photo: Lay Long

The Cambodian and French team worked on the statue on the grounds of Department of Safeguarding and Preservation of Ancient Buildings compound, previously known as Conservation d’Angkor, where fragments of statues and sculpted features were stored for nearly a century in Siem Reap city. Photo: Lay Long

As Chamroeun explained, the Cambodian-French team members believe that this statue has been the hardest they ever had to restore. Although, the work went relatively smoothly after the reassembling of the back and two pieces of the chest.

During the process, the team first reassembled body parts with two thighs. Since many inner parts couldn’t be found, these experts used a red paste to form a new layer for the statue as well as to cover the steel structure that was used to support the statue. The RenPaste epoxy modeling paste is as strong as wood but as light as paper, Chamroeun said.

“It didn’t add weight to the statue, so we decided to use it,” he said. Three other faces made of RenPaste were attached to the statue. Several layers were added over the paste before affixing them to the stone.

Over the years, Chamroeun has been involved in the restoration of many temples in Angkor Park. However, reassembling the stones of a temple was never as hard as working on this statue of the Dancing Shiva, which might be the biggest statue of this kind in Asia, he said.

A temple has a clear structure such as a roof, walls and foundation: When a stone falls down, it is fairly easy to locate its place, Chamroeun said.

“But this statue was chiseled, not falling down,” he said. Based on the traces found on its body, it is believed that the looters thought something valuable might have been put inside the statue, he said.

The restoration team has meant to complete the work in 2024, that is, this year at the latest. The French team has suggested displaying the Dancing Shiva inside a hall near Krahom Temple where it was found at the Koh Ker Archaeological site, along with the remaining stones, or even build a museum there to exhibit this masterpiece, Chamroeun said.

Wherever the authorities decide to display the Dancing Shiva, “it will be spectacular,” he said.

And wherever the statue is displayed, the location will have to be able to accommodate its height, he said.

Reflecting on this long and challenging project, Chamroeun said that Cambodian and French experts are happy to have been able to restore the statue to its current state.

“If we had no love or were not willing to sacrifice, it would have been difficult,” he said. “This project requires time, techniques and skills.”

As archaeologist Chhan Chamroeun explained, it is far easier to find the location of stones fallen from an Angkorian temple than to piece together fragments of a statue. Photo: Torn Chanritheara

As archaeologist Chhan Chamroeun explained, it is far easier to find the location of stones fallen from an Angkorian temple than to piece together fragments of a statue. Photo: Torn Chanritheara

The statue originally had five faces on a two-level head: one on the top, and four on the right below the top one with 10 hands. Photo: Torn Chanritheara

The statue originally had five faces on a two-level head: one on the top, and four on the right below the top one with 10 hands. Photo: Torn Chanritheara

Sem Vanna contributed to the story.