Laos: Taking the Homegrown Way to Self-Reliance in Food

- By Vannaphone Sitthirath

- September 26, 2023 12:06 PM

VIENTIANE | “I want to change the idea that being a farmer is poor. I want to show people that farmers are the ones who can help create nature’s abundance,” said Chanthaly Deeyangwuay, who runs her family’s organic farm in a village south of the Lao capital.

Somchit Phankham, for her part, took on the challenge of turning a donor-started farming project into a social enterprise that is also a hands-on school of on organic agriculture for young farmers from all over Laos. Sustainable farming cannot only be about the environment but must generate “enough income as well” for it to take root, she points out.

Their homegrown initiatives aim for a more balanced way of living - where people live with the natural world, instead of just taking from it, in ways that are aligned with social and economies realities in this country of over 7.5 million people.

While sustainability is often equated with the climate crisis, decarbonisation or the energy transition, in Laos, a least developing country where 58% of the labour force works in agriculture, it is intertwined with the need to navigate rising living costs at a time of economic uncertainty.

In the last year or so, soaring inflation has been eating into people’s incomes. This has pushed up the prices of fuel, fertiliser and consumer goods at a time of rising world prices of commodities, the sharp depreciation of the Lao kip and what the World Bank says is weaker capacity due to debt challenges.

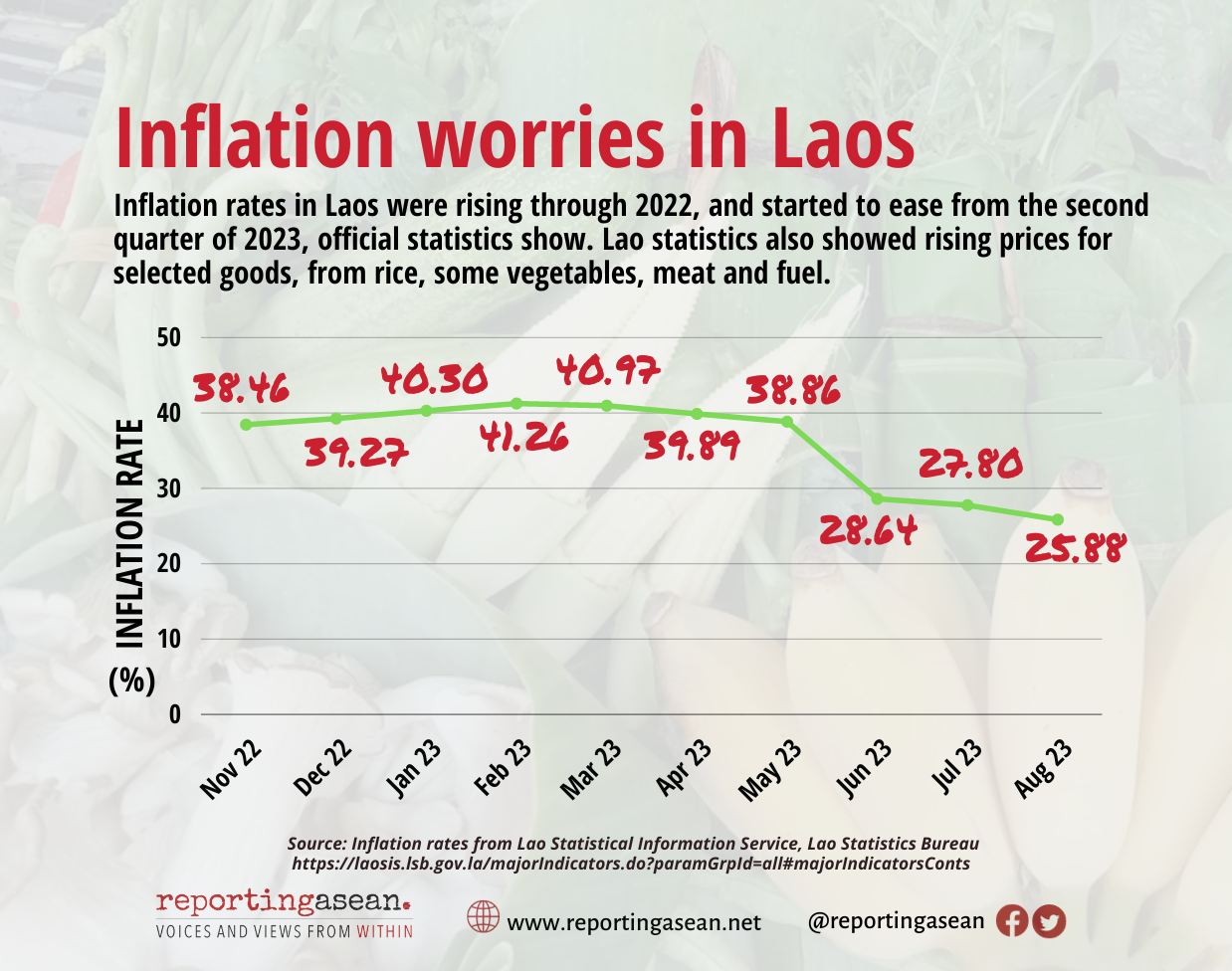

Inflation peaked at 41.26% year-on-year in February this year, figures from the Lao Statistics Bureau show. It hovered at 40% or so until April, levels that were the highest in more than two decades. Inflation has since been easing, and was at 25.88% as of August.

Meantime, Laos’ monthly food index continues its upward curve, World Bank data show. It stood at 1.71 as of mid-September, the highest in over a decade, including during the pandemic.

In August, the Lao government announced a nearly 25% increase in the monthly minimum wage from 1.3 to 1.6 million kip (67 to 83 US dollars), starting October, to help citizens cope with the economic situation. This is the third wage hike since June 2022.

“In response to inflation, more than three-quarters of affected households reduced food consumption or switched to cheaper, self-produced, or wild foods. This could lead to poor food and nutrition security,” said the World Bank’s Lao Economic Monitor in May. “By the end of 2022, 64 percent of Lao families were living on the same or a lower budget than a year earlier,” it said.

In this context, Chanthaly and Somchit’s stories offer ideas around what may help reduce households’ vulnerability to external economic factors.

Revisiting traditional ways and updating them – such as ensuring crop variety and avoiding the heavy use of chemicals - may provide tools that help restore the balance between humans and their environment, says Khamlar Phonsavat, an independent environment consultant who has worked with international agencies.

“Organic farming will be safe for both farmers and consumers and will help reduce the negative impact on the environment,” she said, in addition to easing pressure coming from the increased costs of products and raw materials due to currency fluctuations.

As Laos became more integrated with the global economy, the country “changed its way of doing agriculture from self-sufficiency and depending on nature to producing volumes big enough for distributing to markets,” Khamlar explained. This shift saw farmers turning to chemical fertilisers, apart from newer technology, to boost volume and productivity.

GROWING FOOD

These days, pictures showing edible snails and catfish, mushrooms, wild fruit and herbs fill the Facebook feed of Phommalok farm, whose name means ‘kindness to humans’. Other posts show photos of ponds whose surfaces are bright green with ‘nae ped’ leaves – the farm’s way of feeding fish and frogs and relying less on commercial feed.

“Our life is not luxurious, but full of happiness and freedom,” read one post, which went with photos of children riding buffaloes and a family having a meal.

Located in Pakngum district some 40 kilometres south of Vientiane capital, Phomamalok was not always in organic farming, says Chanthaly Deeyangwuay, who runs the farm that her father started in 1992, the same year she was born.

For years it had gone the way of many farms in the community, and used chemical fertilisers, along with natural ones, to cultivate the same crops in between rice harvests year after year. Soon, the family saw a deterioration in soil quality. They also realised that they were selling products from the farm, which had rice, some vegetables, fish and livestock without thinking of their basic needs, and were ending up buying food and other items.

In 2010, Phommalok shifted to organic means of growing agricultural products, using local practices and low-input resources. Chanthaly describes this as a way that is “safe for our health and provides enough food to feed our family before selling the surplus”.

Phommalok’s story is also a personal one for Chanthaly, who says she realised that she belonged to rural life while studying for her sociology and social development degree at the National University of Laos. “I felt inferior during my first two years at university,” she said. “As I come from a remote area, people called me ‘khon ban nork’ (country bumpkin).”

But to her, village life meant something else. “Back home, we have food even though we do not have money,” she said. “In rural areas, people depend less on money. They can grow food for themselves, such as rice and vegetables, while in the city, people mostly buy food,” explained the 31-year-old Chanthaly. “If they want to eat good food, they have to pay more – and we’re not even sure if those so-called good food are really good.”

In the family farm today, Chanthaly said, “We can see the difference - the water, soil and forest are healthier. The ricefield ecosystem is better.” She added, “I want to prove that we can earn income by ourselves in our own village.”

FROM PROJECT TO BUSINESS

Organic agriculture is also the focus of Panyanivej organic farm, whose owner and manager Somchit Phankham acquired it in 2014 to see if she could make it fluorish over the long term.

The eight-hectare farm, located in Ban Samketh, Sikhottabong village in Vientiane capital is a spinoff from a project that a local non-profit, the Participatory Development Training Centre (PADETC), set up six years before. “Usually it (organic agriculture project) is supported by a project,” Somchit said, and "when the project ends, the activity tends to end as well”.

She recalls having been curious about why many organic farming projects fizzled out, and why Laos relies sizeably on imported rice and vegetables despite being rich in agricultural land.

“Organic agriculture, for me, is where Laos’ roots are,” said Somchit, who used to work on PADETC’s education programme. “Our ancestors lived close to nature and our local food are very much (sourced) from the field and the forest.”

Panyanivej, a name that combines ‘panya’ (wisdom) and ‘nivej’ (ecology), wants to live by these values and pass them on in today’s fast-paced economy, she says.

Five hectares of the farm are planted to rice of different types - the white, brown and sticky varieties - and two hectares host diverse vegetables and fruit trees, from spinach to mulberry and bananas that are cultivated by rotation. Composting is used to produce natural fertilisers.

Apart from selling produce, Panyanivej also provides training to students from the local agricultural college and has hosted more than 60 of them thus far. It employs five farmers, in their twenties, who have backgrounds in agriculture. It hosts open classrooms for local students, and interested tourists.

Nearly a decade after turning a project into social enterprise, Somchit says that a sustainable business model needs to balance four elements - social, economic, environmental and heart. “There is much more to develop and endless work to do when we are a social enterprise because we are not only working on the social and environment part, but we must work hard to generate enough income as well,” she said.

Phommalok and Panvanivej highlight how acquiring more self-reliance at the individual level, by producing more of one’s own food, can seem small but have potentially big impacts at a time when sustainability is very much about meeting basic food needs. For many these days, eating well means living well.

“Working just to earn money alone is not worth it,” Chanthaly said. “Apart from [bringing in] money, work should be able to give us happiness, freedom, good health and be able to support others and create value in other aspects.”