Indonesia’s Buddhist History: A Khmer Insight

- By Sao Phal Niseiy

- November 22, 2022 4:46 PM

Cambodian scholar Khath Bunthorn has a deep interest in Buddhist philosophy and has embarked on a journey to write a book on the roots of Buddhism in Indonesia in Khmer language. Bunthorn holds a bachelor of arts in political science and a master of arts in international relations from Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. In 2013, he was awarded a Government of India scholarship, ICCR, to pursue MPhil and PhD programmes at the Center for Southeast Asian and Southwest Pacific Studies (later renamed to Centre for Indo-Pacific Studies), School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Cambodianess’s Sao Phal Niseiy interviews him on his journey in writing the book as well as his plans for publication.

Sao Phal Niseiy: You wrote a book titled “History of Buddhism in Indonesia: Past and Present”. Can you tell us a little bit more about the book?

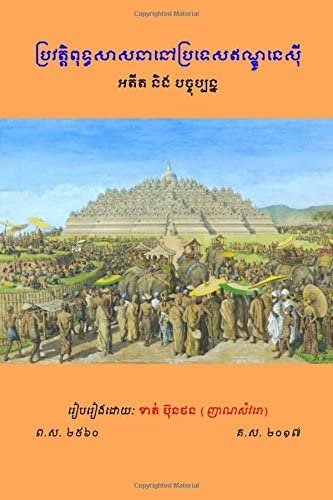

Khath Bunthorn: It is timely to talk about Buddhism in Indonesia since the largest Southeast Asian nation takes the rotating chair of ASEAN 2023 after Cambodia successfully chaired ASEAN 2022. Actually, the book is a byproduct of my pilgrimage to the world’s largest Buddhist temple of Borobudur, Indonesia, in 2016. It explores the historical rootsof Buddhism in the Indonesian archipelago during different kingdoms – Srivijay and Majapahit – which ruled the Suvarnadvipa or Island of Goldcentered around Java and Sumatra islands.

However, the main focus is on the Buddhist revival in Indonesia, the Buddhist reconciliation with the first principle of the official philosophical foundation of Indonesia, and the current practice of this ancient religion there. It also looks into the development of the country’sBuddhist education and its link to international Buddhist networks.

A significant portion of the book is devoted to Borobudur from different perspectives – cultural diplomacy, archaeology and tourism. In short, the history of Buddhism in Indonesia can be described as “rise, demise, and rise”. It concludes with the positive remark on the future development of Theravada Buddhism in the most populous Muslim-majority country.

Sao Phal Niseiy: What prompted you to write the book?

Khat Bunthorn: It happened by accident. At that time, some friends invited me for an ambitious trip to countries in Southeast Asia with Indonesia as the main target because the country’s Buddhist leaders were to hold the International Tipitaka Chanting and Asalha Mahapujaceremony. We began our trip from Thailand (Chiang Mai) to Malaysia and then Singapore before we arrived in Indonesia’s special region of Yogyakarta and Central Java, where ironic Borobudur is located.

As I agreed to the invitation, I started my readings on Buddhism in Indonesia and Borobudur so that I could tell the story about it to my co-travellers, especially upasika Sok Nary and her husband. The more I read, the more I gained interest. While attending the three-day International Tipitaka Chanting and Asalha Mahapuja ceremony at the foot of Borobudur, Magelang, Central Java, I carefully observed the ongoing Buddhist function and wrote down my diary. I was particularlyimpressed by the way the Indonesian Buddhist youths respect monks; notably, while talking with monks, they keep their palms together (Pranama). Moreover, the long row of the Buddhist procession throughthe city amplified the strong existence of Buddhism in Central Java. I also noted the dark-yellow dress of Indonesian Buddhist panditas (equivalent to acharya in Cambodia), which is unique to the country.When I returned to India, I had a keen interest in reading more aboutIndonesian Buddhism, and thus I decided to write a book about it for the benefit of the readers.

In fact, Buddhism is a pan-Asian religion in the sense that it is a powerful factor in shaping Southeast Asian cultures. As Cambodian Buddhists, we should know more about the history of our religion in the region through which we can connect and reconnect with one another.This is the objective of writing the book.

Sao Phal Niseiy: Currently, there is only Khmer version of the book. Do you intend to only entice Cambodian readers, or do you also plan to have it in English version?

Khath Bunthorn: Some people who read the book have encouraged me to have it in English for broader access. That is not impossible, but it requires very hard work to translate a book of 300 pages-plus from Khmer into English. Thus, I am open for any interested agents and publishers to take responsibility.

Sao Phal Niseiy: According to the book, Buddhism vanished in the fifteenth century after the arrival of Islam. How did the country manage to achieve the revival of Buddhism and continue to accommodate the practice in a Muslim-dominant society?

Khath Bunthorn: Although the historical evidence shows that Indonesia used to serve as the high learning centre of Buddhism, the ancient religion disappeared from the island for about 500 years from the fifteenth century to the twentieth century, in order words, from the establishment of the Islam kingdoms to the Republic of Indonesia. Since the colonial period, the Buddhism revival process took different stagesand involved many devoted leaders. During the Dutch colony, Buddhism was almost invisible, and only a small number of Chinese immigrants practised Buddhism.

The first stage involved these Chinese immigrants and the Europeanswho were members of the Theosophical Society and were interested in studying Asian cultures and religions. The Society played an important role in the revival of Buddhism by incorporating the Buddha’s teaching into its curriculum, among other subjects. By 1930, its membership comprised 50% Western, 40% Indonesian and 10% Chinese. In 1932,the Theosophical Society organised Waisak Day at Borobudur for the first time in modern history. One member of the Society deserves mentioning here is Mr Kwee Tek Hoay, a Peranakan Chinese popularfor his novel and literature writings. In 1932, he started a monthly magazine named Mustika Dharma in Bahasa Indonesia. It published content related to religion and philosophy; Buddhism and Confucianism were included. It also published ten serial books on the Buddha’steaching, which significantly contributed to the revival of Buddhism in Indonesia.

We also see the work of Europeans as an important contribution to the restoration of Buddhism during the colonial period. Ernest Erle Power and Yosias Van Dienst established the Java Buddhist Association in Jakarta in 1932; they served as the president and vice president of the association, respectively.

During the same period, the most notable figure was the eminent Dhammaduta from Sri Lanka, Bhikkhu Narada Mahathera. He was invited by Mr Kwee Tek Hoay and the Theosophical Society to Indonesia in 1934. He was recognised as the first Theravada Buddhist monk to arrive in the Indonesian archipelago in 1000 years or at least 450 years. During his twenty-one-day visit, he travelled to major cities such as Jakarta, Bogor, Bandung, Yogyakarta, and Sulo. Importantly, he visited Borobudur temple and there he planted a sacred Bodhi Tree he brought from Sri Lanka in front of the local Buddhists. His Dhammaduta mission attracted the gathering of three major groups of Buddhists for the first time, including two Chinese ethnic groups, Peranakan and Totok, the Java Buddhist Association, and the Theosophical Society. Indonesian Buddhists considered Bhikkhu Nara’s historic visit a golden opportunity to revise Buddhism in their homeland.

Second, when Indonesia gained independence from the Dutch in 1945, Buddhist practice had to adapt to the changing situation in the country.By this time, the ancient Javanese religion gradually appeared in society.The next step was the struggle of Buddhist leaders for recognition of Buddhism as a national religion with Indonesian characteristics.

The Republic of Indonesia has adopted the five principles of the national ideology known as Pancasila, one of which is related to “Belief in the One and Only God”, or Ketuhanan Yang Maha Esa. Interestingly, its official national motto, “Unity in Diversity”, or Bhinneka Tunggal Ika,has been taken from a poem of a famous Hindu-Buddhist scholar of the Majapahit Kingdom, Mpu Tantular. Even though the motto reflects the country’s recognition of the diversity of cultures, regional languages, races, ethnicities, religions and beliefs, the state ideology of Ketuhanan Yang Maha Isa, believing in one God, comes in contrast to nontheistic religions that do not believe in Creator God, particularly, Buddhism.However, as monotheistic religions, Islam, Christianity and Hinduism faced no such issue with this belief. Hence, Buddhist leaders must re-interpret their faith according to this national philosophy, and theysomehow succeeded in doing so, but deep division among themselves remains.

It should be noted that the revival process had been handed over to indigenous and Chinese Buddhists, while Europeans naturally disappeared after the decolonisation of Indonesia. Venerable Bhikkhu Ashin Jinarakkhita, the Indonesian Chinese and the first Indonesian Theravada monk who was ordained as a Bhikkhu in the Burmese Buddhist tradition, was widely recognised as the great Buddhist leader in post-independent Indonesia, whose tireless work was to protect, promote, and propagate the Buddhasasana in conformity with Indonesian national characteristics. To this end, he established Buddhayana, a syncretisation of the three main Buddhist sects, Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana.

In the 1950s, Buddhist activities remarkably increased. Many pagodas were built. The influence of Buddhism re-emerged, which led to a conversion of religion among the Indonesian indigenous people, especially among the former Shiva-Buddhists, who remained after the fall of the Hindu-Buddhist empires. Various publications were also madeavailable in Bahasa Indonesia. In particular, the development of the governing body, the Indonesian Buddhist Sangha, also began.

It is important to recall that in 1959, Ashin Jinarakkhita invited thirteen eminent Theravada monks from Asia, including Cambodia, Thailand, Burma, and Sri Lanka, to establish international sima, to attend Waisak Day, and to ordain more Buddhist monks. Two of the thirteen invited monks were Samdech Chuon Nath, the Supreme Patriarch of the Cambodian Mahanikaya Buddhist order, and Venerable Preah Maha Oung Mean (a former student in India). This was the most important event in the trajectory of the restoration of Buddhism in Indonesia.

Considering the religious conformity to the state ideology, Ashin Jinarakkhita believed that Sanghyang Adi Buddha was a God Buddha; literally, there was a God in Buddhism. He drew this concept of God from Tantra Buddhist text. However, this theory caused controversy in the Indonesian Buddhist community, especially as it was rejected by Theravada monks, who instead came up with the idea that Nirvana was a God in Buddhism.

In addition to the above issue, the practice of Buddhists, especially monks, to free themselves from worldly affairs by thriving to attainNirvana, was alleged to have undermined the momentum of national development. Then, at every Buddhist meeting, government officials stated, “Do not fly from the world, but to participate in the development of the world and contribute to the nation’s struggle for progress” (p. 17).

In May 1978, the Minister of Religious Affairs, Alamsyah Ratu Perwiranegara, met with leaders of all Buddhist leaders in Indonesia. At that meeting, to accommodate the state ideology, the Sangha Council stated that all sects of Buddhism should be based on the belief in one God but maybe with different names (monotheism). So, Ashin Jinarakkhita’s followers believed in Sanghyang Adi Buddha as God, whereas Theravada’s followers believed in Nirvana as God as per their interpretation of Buddhism. At that meeting too, the Sangha Councildecided to establish the Indonesian Buddhist Council as an institution representing Buddhism in relations with the state, named Perwalian Umat Buddha Indonesia, known in short as Walubi. Under these circumstances, all Buddhist organisations or associations must become members of Walubi in order to carry out their work. They are subject to various statutes in order to become members. Walubi is a federation of three Indonesian Buddhist Sangha councils: Sangha Theravada Indonesia, Sangha Mahayana Indonesia, and Sangha Agung Indonesia(Buddhayana).

An ancient Indonesian literature predicts that Buddhism in Indonesia would vanish and rise again after 500 years after the fall of the Majapahit Empire in 1478 CE. It seems to be true. After going through many generations, namely the Islamic kingdoms, the Dutch colonial power, and the independence period, Buddhism began to reappear onSuvarnadvipa. Under the New Order of President Suharto (1967-1998), the government recognised Buddhism as one of the five official religionsin Indonesia, others being Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, and Hinduism (later, in 2006, Confucianism included to become the sixth recognised religion). This recognition was legalised through the Decree No. 45/1974 of the President of the Republic of Indonesia and theDecision No. 30/1978 of the President of the Republic of Indonesia on establishing the Directorate General of Community Guidance of Hinduism and Buddhism in the Ministry of Religious Affairs.

From the fall of the Majapahit Empire in 1478 to the date of the finalDecision in 1978, the interval is exactly 500 years. More importantly, in 1983, the Indonesian government designated Waisak Day as the ‘Day of Justice’, and it became Indonesia’s public holiday. Moreover, the annual celebration of Waisak Day at Borobudur became an international eventwith thousands of participants, including high-ranking government officers and foreign dignitaries.

Notably, most Indonesian Muslims, Javanese Muslims in particular, are believed to be moderate. They consider Buddhism and Hinduism to be ancient religions of the country. With the significance of the ninth-century Buddhist temple of Borobudur as a tourist attraction and part of the country’s cultural diplomacy, Indonesian leaders need to also engagesome two million Buddhist population in the country. Since independence, many heads of state visited the ancient temple, including then-Prince Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia (in 1959 and 1984). Thus, Buddhists are free to practise their faith like the followers of other state religions as they have integrated well into Indonesian society and contributed to national development.

Sao Phal Niseiy: How hard it was to write such a book?

Khath Bunthorn: It is hard both in writing and publishing. First, imagine I hailed from Cambodia and studied in India but wrote a book on Indonesia, a thousand miles away from each other. From an academic perspective, it is of a high risk of error and too brave to embark on such an unfamiliar task. The translation and transliteration of Bahasa Indonesia into Khmer was done with extreme caution. It was even more challenging when effort had been made to write as academically as possible. It had to rely on a myriad of references – primary and secondary sources. However, my class readings on the Modern Politics of Southeast Asia, my interaction with some Indonesian friends in India, and my trip to the island could mitigate the risk.

Second, writing is, of course, time-consuming. It took me about a year before the manuscript could be finalised, and simultaneously I had to write my PhD thesis chapters, which have little in common with the book’s contents.

Third, there were technical issues. I faced some problems with our Khmer Unicode, which at that time, was not properly supported on the computer system (MacBook) For example, the text was erroneously altered when being saved in PDF format. This problem may not be common to other computer users, however.

Another technical issue is that the book was intended to donate to most Cambodian overseas people whom I personally know. I was thinking ofpublishing it in New Delhi and sending it to them, but this would becostly. I am a bit of a tech geek, passionate about computers and the internet. By googling, I discovered that Amazon, a US e-commerce firm, provides a platform for self-publishing. I signed up for it. But Khmer Unicode is not a supported language of the Amazon E-book platform. It was challenging initially, but I could successfully do it by converting the text to images and then PDF. In the image-converted PDF format, the book could be uploaded to the online account. Now the book remains on Amazon, but the same process is no longer working because Amazon has changed its publishing platform. For authors of Khmer language books to have their works on this popular platform, they have to wait until Khmer Unicode is accepted in global E-book platforms like Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) and Apple Books iTunes Connect.

Last is the financial issue. Every work needs financial resources. The expense of book writing and data collection was solely on my own, though I was really happy to do it. However, book printing for free distribution relied on minimal donations from a few dozen good-heartedpeople, and I sincerely acknowledged their benevolence.

Sao Phal Niseiy: Do you have other plans to write more books? If so, what will they be all about?

Khath Bunthorn: I have to say that I really like my first book. I believe itis the first comprehensive book on Indonesian Buddhism ever available in Khmer. I dedicated it to Buddhism under the shadow of which I grew up and was educated. For your information, the book has been revisedand improved for republication in Cambodia. More often than not, when we start writing the first book, we already think of the second one. Since 2019, I have been working on my second book on the prominentBuddhist monks of Cambodia who pursued their higher studies in India in the past, such as Samdech Preah Maha Ghosasananda, Maha MeasChan, Maha Am Suon and many others. I believe their life story and legacy will inspire the new generations of Cambodian students in India and beyond, while also reflecting the close relationship between Cambodia and India through Buddhism in the good old days. Again, it will be published in Khmer, hopefully by mid-2023.