Cambodia Celebrates the 50th Anniversary of Ratifying the UNESCO Treaty on Cultural Property, and Takes Stock of its Victories and Ongoing Battles to Get its Antiquities Back

- By Michelle Vachon

- September 25, 2022 7:15 PM

PHNOM PENH — When it comes to the repatriation of stolen antiquities, Cambodia has become a model to many and a pain for others.

A model as the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts keeps showing that even a small country with limited resources and having had to deal with sombre historical circumstances (the Khmer Rouge genocide and the civil war of the 1970s and 1980s) can conduct a campaign to repatriate its antiquities. And be successful at it, leading the country to share information on this issue with other countries in the region such as during the ASEAN International Conference on the Prevention and Control of Illegal Trade in Cultural Property that Cambodia hosted in Siem Reap city in mid-September 2022.

In the process, the country has truly turned into a pain to some as Cambodia’s policy and measures have basically destroyed the illegal market in Khmer antiquities, putting dealers at risk of prosecution and making it far less prestigious for collectors to own works that can now be easily identified as the stolen heritage of a country. Moreover, some prestigious museums in the United States, the United Kingdom if not Australia may have to revisit their acquisition policy in general and how they have acquired Khmer works in particular not to see their reputation questioned.

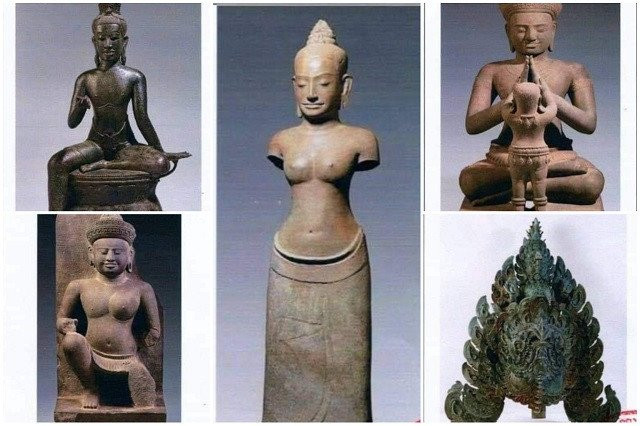

In the meantime, the publicity around the ongoing U.S. authorities’ seizure of trafficked Khmer works does not bode well for the illegal Khmer antiquity market. The latest event was a ceremony held in New York City on Aug. 8 to mark the imminent return of 30 Khmer works seized by the U.S. authorities.

Cambodia’s strategy has included implementing measures within the country such as the heritage police—Cambodia being one of the rare countries in the world along with Italy to have such specialized police corp.—and working with foreign legal and law enforcement authorities such as those of the United States to track down and recover pre-Angkorian and Angkorian artworks.

Of course, Cambodia is a signatory of the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. Adopted in 1970 by the General Conference of UNESCO, it was ratified by Cambodia on Sept. 26, 1972. As the country was plunged in a civil war and the Cambodian government armies were fighting the Khmer Rouge officially headed by King Norodom Sihanouk based in Beijing, Cambodian parliamentarians had taken the time to review and approve this convention to help protect the country’s heritage.

Cambodia was the 7th country in the world to ratify the convention— https://en.unesco.org/about-us/legal-affairs/convention-means-prohibiting-and-preventing-illicit-import-export-and —and in June 2021, Minister of Culture Phoeurng Sackona was invited to join a UNESCO representative to pronounce the closing remarks at the Asia–Pacific Regional Conference held in Bangkok and marking the 50th anniversary of the convention. Years after Cambodia, the United States would ratify the convention in 1983, Australia in 1989 and Great Britain in 2002.

Preserving one’s heritage is a mission that Cambodia is now inviting countries in the region to share. “The theft and illicit trafficking of cultural property is an international criminal activity, only surpassed by drugs and arms trafficking: It is a major multilateral challenge that has to be addressed by all ASEAN countries,” said Foreign Minister Prak Sokhonn on Sept. 5 during the conference on the prevention and control of illegal trade in cultural property held by the country as chair of ASEAN. “Cultural traditions are an integral part of ASEAN’s intangible heritage, and it is an effective means of bringing together ASEAN peoples to recognize their regional identity…Acting together, we can and we will address this challenge,” he said.

Cambodia’s ongoing efforts to recover its antiquities

Over the last few years, the publicity around the ongoing U.S. authorities’ seizure of trafficked Khmer artworks has not boded well for the illegal Khmer antiquity market. Moreover, the series of reports produced by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which involved journalists from more than 150 major media across the world, has exposed in late 2021 and continue to reveal how extensive the trade in Khmer artworks was for decades and how many major museums throughout the world may have illegally-acquired works.

In a report aired on Australian Broadcasting Corporation radio news on July 17, 2022, journalists described how a collector and an art gallery in Australia obtained Khmer antiquities from an art dealer in Bangkok who was working with Douglas Latchford and the tricks the dealer and Latchford would use to ship those works to various countries without raising questions— https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-07-17/secret-history-australia-thai-cambodian-art-antiquities/101054392. The art gallery is believed to have sold Khmer works to museums in Australia as well as in the United States.

A British art dealer and collector based in Bangkok, Latchford was indicted in 2019 in United States for fraud and for smuggling Cambodian artworks from the pre-Angkorian and Angkorian eras. He died in August 2020 before facing trial on federal charges brought by the U.S. Justice Department.

Museums’ responses to the press coverage have differed. Following the news reports linking to Latchford four Khmer artworks the Denver Art Museum in United States had acquired, the museum authorities immediately went about returning those works to Cambodia. The Cleveland Museum, which had purchased some Khmer works in Great Britain from an auction house with links to Latchford, signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the National Museum of Cambodia and, in 2021, held in cooperation with the museum an exhibition of Khmer artworks with some of them being lent by Cambodia.

However, The New York Times reported on Aug. 18, 2022 that, while Latchford sold and/or donated 13 Khmer artworks to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the museum has so far refused to show the Cambodian authorities its paperwork on those antiquities— https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/arts/design/met-artifacts-cambodia.html . According to the news story, Cambodia has requested the assistance of the U.S. Justice Department to deal with the museum.

Through the Memorandum of Understanding on “the Imposition of Import Restrictions on Categories of Archeological Material of Cambodia” in effect until Sept. 19, 2023, between the two countries, numerous Angkorian artworks acquired illegally have been seized by the U.S. authorities and returned to Cambodia. A ceremony covered by the media was held in New York City on Aug. 8, 2022, to mark the imminent return of 30 of these Khmer works.

In recent years, Cambodia has stepped up its efforts to track down and recover any Khmer artwork smuggled out of the country and acquired by museums or collectors. A British Broadcasting Corp. (BBC) story by Celia Hatton on May 12, 2022, reported that Minister of Culture Phoeurng Sackona had written to her British counterpart Nadine Dorries about some stolen Khmer antiquities that may now be in two London museums— https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-61354625 .

According to Hatton, the British Museum may have around 100 Khmer artworks or artifacts, the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) more than 50, and both museums said they would respond to the letter they received from the Cambodian government in which are listed the Khmer works the authorities believe they have in their possession. “[Cambodia] simply doesn't have the museum space or resources to take everything back.

“They say they're not looking to empty Western museums of all Cambodian treasures,” Hatton said in the news story. “What they do want is institutions like the British Museum and the V&A to change their signs, acknowledging that these objects belong to the people of Cambodia.”

Cambodia’s relationship with France and its Musée Guimet

The way to determine whether a museum or institution has legally acquired a pre-Angkorian or Angkorian artwork is straightforward: If that museum or institution has not obtained official documentation for the work, that is, an agreement with the Cambodian government, it is being held illegally.

The Guimet Museum of Asian Arts in Paris, which has the biggest collection of pre-Angkorian and Angkorian art outside of Cambodia, has long ago negotiated the terms of acquisition. “The Musée Guimet is involved in long-term loans to exchange art objects with museums in Asia, for instance in Cambodia,” had explained Pierre Baptiste in an interview for The Asia Foundation in 2015— https://asiafoundation.org/2015/06/10/the-museum-as-keeper-of-memory-a-conversation-with-pierre-baptiste/ . Baptiste, who has taught at the Faculty of Archaeology at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh, is senior curator of the Guimet Museum.

“We feel that there should be a balance,” he said. “It is good that art from all countries can be seen everywhere. It is a good way to comprehend the beauty, the originality, and the importance of everyone’s culture. We don’t think that a dogmatic policy of sending collections back where they come from is a good thing, for several reasons.

“In the case of Cambodia, maybe the museum is also a good place to understand how deeply the country suffered from its neighbors, who invaded and tried to destroy the country and divide it,” Baptiste said.

At Cambodia’s request, Cambodia had become a French protectorate in 1863 in order to prevent neighboring countries from absorbing its territory.

As a result, France and Cambodia have shared chapters of history over the last 150 years. For example, some Cambodian soldiers joined the French forces to defend France during the First World War; and the National Museum in Phnom Penh was founded by a Frenchman, Georges Groslier, who was born and died in Cambodia, a casualty of World War II. Then, when King Norodom Sihanouk declared the country’s independence in November 1953, French archeologists who had been restoring Angkor and French researchers who had been studying Cambodia’s culture and traditions since the 1900s kept on doing so. And still do.

However, this long relationship does not mean that Cambodia has been casual about its national heritage displayed in France. In January 2016, when experts found that the body of a pre-Angkorian statue whose head had been exhibited at the Guimet Museum since 1889 was in the National Museum’s collection in Phnom Penh, and that the pedestal of a 10th century Angkorian statue in the French museum’s collection since 1873 was in Phnom Penh, it took an agreement between Cambodia’s Council of Ministers and France’s Ministry of Culture for the statue’s head to be sent to Phnom Penh and the statue’s pedestal to Paris, the two countries agreeing to do this on a permanent-loan basis.

Preserving masterpieces from the past and also protect those of today for tomorrow

“Cambodia has a very specific policy regarding the protection of cultural property: I would even say that Cambodia is the country that is the farthest ahead in Southeast Asia,” said Etienne Clement, a Belgian attorney specialized in international law and cultural heritage law. “That is, there is [in Cambodia] fairly recent legislation dating from the 1990s. A legislation that is tailored to the types of trafficking of which these antiquities are victims. There also has been, over the last 25 years or so, a heritage police force trained, equipped and funded to protect cultural heritage.”

“And there is a policy of systematic recovery of Cambodian cultural assets that are identified outside the country’s borders such as in Europe, the United States and so on,” Clement said. “Therefore, I would say that Cambodia is definitely the country with the most advanced policy.”

A Belgian attorney and career UNESCO official who has worked on the writing of international conventions for the protection of cultural heritage, Clement headed Cambodia’s UNESCO office in the 1990s and contributed to the writing of legislation to protect the country’s monuments and antiquities.

Now a researcher based in Bangkok, he wrote a book on capacity building and methodology to counter cultural objects trafficking in Southeast Asia in 2019 and an overview of antiquity smuggling in Southeast Asia in 2021.

“The most recent development to note is that Madam Minister of Culture Phoeurng Sackona shows an incredible determination to obtain the return to Cambodia of stolen cultural objects: She has made this a key issue, and that’s great,” Clement said.

Regarding the protection of Cambodia’s heritage within the country, he said, monument preservation in the Angkor Archeological Park is well in hand with the government agency Apsara Authority and the International Coordinating Committee of Angkor monitoring preservation and restoration work in the park, he said. But at stake is the park itself now under threat of urban sprawl in spite of the legislation protecting it as part of Angkor being a UNESCO World Heritage Site. “I remain optimistic: The goodwill is there,” Clement said. “But it’s the old problem of having to reconcile public and private interests.”

One problem is the management of the ever-growing flow of visitors at Angkor and all that this entails—from preventing stone damage as thousands of tourists climb the monuments, to controlling vehicle traffic and air pollution. “In this area, there is a lack of national and international expertise [since most experts in the field tend to be archeologists and monument restoration specialists] and a great deal must be done,” Clement said.

Another issue that requires urgent action, as Angkor monuments did in the early 1990s, is the protection of Cambodia’s urban heritage, he said. The country now stands where Europe was about three decades ago when the destruction of landmarks created an uproar and changed people’s views on the preservation of 19th and 20th century buildings. As a result, Clement said, “the notion of heritage evolved to include all of a country’s history. Whether or not one rejects the neo-colonial era, and the glorious and non-glorious periods, they all are part of a country’s history.”

Cambodia could even reap economic benefits from preserving its 20th century buildings, said Clement. Hanoi attracts tourists with its early 20th century neighborhoods; and Singapore, which had demolished many of them, is now rebuilding because of visitors’ interests, he said.

If Cambodia’s 20th century heritage is to be preserved, the Cambodian government will have to make a decision without delay and adopt the necessary laws, Clement said.

Another urgent matter is the cultural sector for which there is hardly any government or international funding, he said. Most resources go into Angkor and some institutions such as the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, and the Faculty of Archeology and Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the Royal University of Fine Arts, leaving artists and arts students with no support and no proper facilities in which to work, Clement said.

The official policy is turned toward the past, making for a cultural sector with no life, he said. “There has to be a balance.” Stands to protect the country’s culture—so much part of Cambodia’s identity—usually are of a negative nature such as decrying foreign influences, Clement said.

The next step could be a cultural strategy complete with budgets, he said. As for a public for Cambodia’s arts and artists, Clement said, there already is a demand on the part of Cambodians, foreigners living in the country, and tourists