A Book Reflects through Photos the Complexity of Cambodia’s History since 1866

- By Teng Yalirozy

- October 27, 2022 3:28 PM

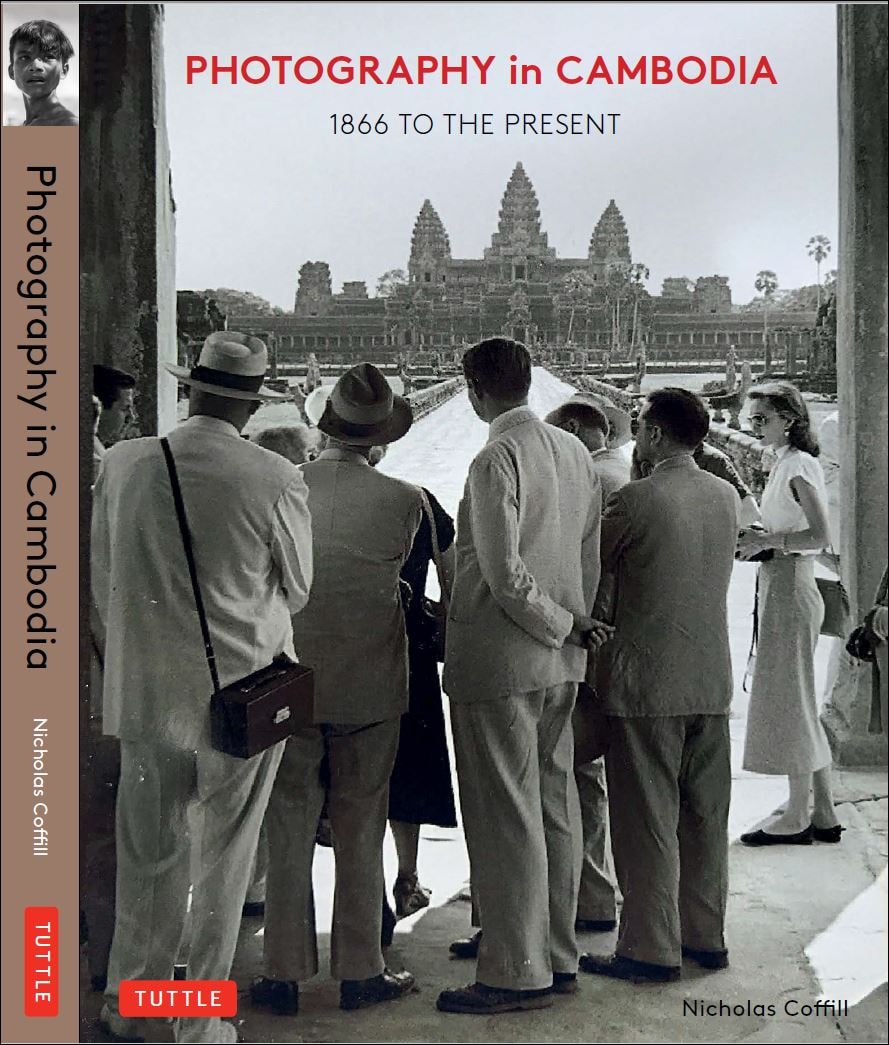

PHNOM PENH — As a French quote goes, “the history of the past interests us only in so far as it illuminates the history of the present.” A book on photographs of Cambodia over the last 170 years was compiled with this in mind, to enable the readers to understand the complexity and beauty of Cambodia’s history through images of its kings, its people’s struggles, and the road to recovery.

“Photography in Cambodia: 1866 to the Present,” illustrates the country through photographs taken in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

Written by Australian designer and social history narrator Nicholas Coffill, the book depicts in details the country's history from the early stages of the French Protectorate through World War II, the country's fight for independence, the short-lived Khmer Republic, the genocide of the Khmer Rouge regime, and its reinvention as a modern state in Southeast Asia.

“Most history books that are about Cambodia are mainly texts, and very few of them have photographs,” Coffill said in an interview on Oct. 24. “I thought it was important for readers of Cambodian history that they also got the photographs to help illustrate and give a kind of nuanced view or vision of what Cambodia's history was about.”

The book consists of nine chapters with around 500 photographs, amounting to a visual record of the country’s history, with the photographs evenly distributed across the nine chapters that cover the last 170 years.

His goal, was, as he explained, “to give a raft of an equal amount of photography of each section of Cambodia’s history. I did not want to favor one era over another. I wanted to level things out.”

Coffill went on to say that, at times, there is a contradiction or a difference between the visual record and what has been written by historians. Thus, he was keen to create a nuanced history of Cambodia. “By looking at four or five photographs, you can get quite a complex understanding of the major events in Cambodian history over a certain period of time,” he said.

Photographs of Different Photographers

The photographs set in the 19th century during the French Protectorate, were mostly taken by French people who worked in France’s public service and were employed as administrators or explorers in Cambodia, Coffill said, plus a few entrepreneurs who traveled for the sake of photographing.

From 1866 through 1871, Émile Gsell was the first to capture images of the performers at the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh—his photos today are mainly in France, Coffill said. The first European to photograph the Angkor Wat temple was John Thomson, and his collections can be found in museums in Great Britain.

In the 20th century, after the First World War, photographers of many nationalities came to Cambodia as travel was affordable. French, British, American, and Swiss photographers visited the country.

Photo provided

Photo provided

During World War II, Japanese photographers came to the country—the French government had aligned with Nazi Germany and its ally Japan in the conflict. Most of these photographers were women who had been privately funded to come to Cambodia and explore.

After the war and during the U.S.-Vietnam war, more and more American photographers were seen and the number of Cambodian photojournalists progressively increased. From the late 1960s up to 1975, few photographers remained in the country as only some local photographers plus foreign journalists and photographers sent to cover the events were left. During the Khmer Rouge regime, photos were taken on the authorities’ orders.

“In the 80s, we had Vietnamese, French, British, and Americans [photographers] all returning to the country after Pol Pot [the Khmer Rouge Regime] was kicked out of Phnom Penh,” Coffill said. And in the 1990s and the 21st century, more Cambodians have become photographers with the improvement of the living conditions and, more recently, the rise of smartphones.

Production and Challenges

When Coffill started working on the book, he said, “I knew that I had nine chapters, I knew that I wanted to be fairly equal with the amount of photographs for each section.”

First, he had to read and then read more on the history of Cambodia as he wanted to cover the subject from various angles to better reflect each era.

Plus, Coffill said, since he wanted the book to be for the general public, the period for which there was the most photos was not necessarily the most important one as far as he was concerned, Coffill said. “Trying to find the mainstream was considered the most important part of photography, and then doing your own research on whether they need balance or counterbalance,” he said.

As there has been no research on the whole history of Cambodia’s photography over 170 years, Coffill had to filter the information provided because collections in France or Cambodia or private collections did not provide a balance between the overall history of photography and photography in Cambodia.

“So I had to make that balance to decide within the collection of 16,000 photographs held at the French School of the Far East [École française d'Extrême-Orient or EFEO], which of these 16,000 photographs to put in the book,” he said. “So, what seven or eight photographs should I choose that I think are representative of their contribution and representative of Cambodia and photography?”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Coffill ended up having to spend two years in Australia, which actually gave him the opportunity to focus on research for the book, he said. Since the pandemic made it difficult to travel to collect the photographs, Coffill had to work online, accessing museum and private collections in Australia, Malaysia, Singapore as well as Cambodia to gather photographs.

His real challenge, however, was doing online research for the photographs and obtaining permission to use the photographs. “You have to navigate different websites, various museums, and archives,” Coffill said. “Each of them organizes the materials in a different way. So, it is not consistent, which was often frustrating to navigate the websites. […] It took a long time to get a hold of a particular image and approval to reproduce that image.”

The next process, Coffill said, was the payment. When he got a receipt, he had to go back to the national archive to give the receipt so that the image he bought would be sent to him. The most expensive photo was about $150, but many photos were given free by friends or available for free through certain archives. “I wanted a big variation of images,” he said. Therefore, while some photographs came from museums, others were bought online through auctions or eBay.

The book took Coffill about three years to complete, with six months working out the structure, the pitch, and the level of English of the book while the detailed research took about 18 months. Then, the production of the book and working with the publisher took him one year to turn the collection into the physical book.

Nicholas Coffill is an Australian designer and social history narrator. Photo provided

Photographs Reflect Feelings

Nicholas Coffill admits that his favorite photograph is one taken in 1961 by the late Michael Vickery—an American historian who specialized in Cambodia and Southeast Asia history—who was a school teacher in Battambang province at the time. He photographed four friends relaxing near rice fields.

“It shows to me what a friendly relationship he, as a teacher, had with his students, and it also shows that, after the Second World War, people were much more relaxed,” he said. “So, this photograph reflects, I think, major cultural change around the world. It reflects the Cambodian muse and foreigners feeling more comfortable and less formal in their relationship with Cambodians.”

Among his other favorites is the photograph of five elderly musicians drinking red wine with in the background a bamboo ladder and, to the left, musical instruments. As Coffill said, they do not look very drunk but seem to behave as if they were for the photograph.

“So, this leads us to some interesting questions,” Coffill said. “Who was the photographer and from which culture did he come? If it was a French photographer, were they trying to make fun at Cambodians for being drunk and lazy?”

Or, he said, maybe these musicians were play-acting at being Frenchmen who were known to enjoy red wine, opium, and be rowdy with friends at local French cafés in Saigon and Phnom Penh if the photographer was Cambodian.

“We may never get to the bottom of this question, but it does [show] some interesting examples of humor and play-acting in early colonial photography in Cambodia,” he said.

With this book, Coffill said he wanted Cambodians to see their country’s history through a very clear layout of multiple collections of images and photographs. “Rather than having to read a lot of text, you can have a look at these images put in chronological order and understand the complexity of your country's history just by looking,” he said.

Some photographs from the book are being exhibited through Nov. 13 in Phnom Penh at:

. Meta House (https://meta-house.com/) and

. Pi-Pet-Pi Gallery282 ( https://www.facebook.com/Gallery282/ )

As Coffill explained, some photos could not be exhibited as rights were only for publication in the book.

The book, which costs $39.99, can be obtained at: the Shop of the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh, and at the Minimalist Coffee Shop in Phnom Penh (https://www.facebook.com/minimalistcoffeeandstore/ )